by Jim Donaghey, Will Boisseau and Caroline Kaltefleiter

12th December 2022

[Also available as a podcast at Anarchist Essays.]

The following is an excerpt from the introductory chapter to the newly published book Smash The System! Punk Anarchism as a Culture of Resistance, edited by Jim Donaghey, Will Boisseau and Caroline Kaltefleiter, and published by Active Distribution in December 2022. It is the first volume in The Anarchism and Punk Book Project series.

The connections between punk and anarchism seem obvious to those of us who are bound up in that interrelationship. Our direct experiences shape our perspectives – for all its complications and shortcomings, we keenly appreciate punk’s role as an anarchist education, an anarchist practice, and an anarchist culture. From our viewpoint, it’s clearly the case that anarchism has been revitalised by punk, worldwide, re-introducing anarchist ideas in post-authoritarian contexts in Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe, while the dusty old anarchist movements of Western Europe and North America got a much needed kick up the arse. Ask yourself, what would the anarchist movement be like today without punk’s resuscitating influence?

There are plenty of people out there who will come to the opposite conclusion, who are dismissive of punk’s association with anarchism, and even see it as damaging. For example, in his 2014 book Underground Passages, Jesse Cohn bemoans ‘punk’s cultural hegemony’ (p. 187) within the anarchist movement, complaining that punk’s supposed dominance means that scholarly coverage of it ‘vastly exceeds that given to [Emile] Pouget or the Cinéma du Peuple’ (p. 26). He sets out to correct the record by largely ignoring punk altogether in his otherwise extensive overview of anarchist cultures of resistance, even asserting that punk is ‘culturally limited’ (2014, p. 387) and aesthetically and musically inferior to his own preferred forms of art, music, poetry and theatre – echoing socially constructed distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture.

Of course, there’s no accounting for taste, and no expectation that punk should be the sole expression of anarchist counter culture – a quick overview of contemporary anarchist musics would completely undermine Cohn’s suggestion of punk’s ‘hegemony’ or dominance anyway (think of all the anarchist folk, hip-hop, black metal, electronica or darkwave, for example). But Cohn’s view of punk as a homogenous and sub-standard musical form is an unhelpful, ill-informed stereotype. If we were so minded, we could immediately counter Cohn’s stereotyped perception with an example such as the anarchist band Propagandhi, from Canada, who mutated from 1990s poppy skate punk to their contemporary ‘progressive thrash-metal’ punk, and even won the 2006 ECHO songwriting prize (see SOCAN webpage) with their song titled ‘A Speculative Fiction’ (2005). But we don’t want to fall into the trap of holding punk music up to the oppressive artistic standard of ‘high culture’ – punk music is often at its best when visceral, raw, and immediate. It is a diverse and continuously evolving genre, perhaps better understood as a multiplicity of intersecting genres. Yes, some punk is musically simplistic, sometimes highly derivative (and usually intentionally so), but just because someone doesn’t happen to like a particular musical style, that doesn’t invalidate its wider social and political significance. Cohn suggests, albeit obliquely, that punk is not a ‘proper’ expression of anarchist culture but, to put it frankly, none of the poetry, illustrations, music, plays, novels or films celebrated by Cohn can be argued to have been as influential as punk, however artistically virtuous they may be.

Across the numerous contributions to the Anarchism and Punk Project book series, we have tried to avoid too much musicological framing, precisely because those forms of analysis are so often shaped by the personal tastes and proclivities of the individual writer. We focus instead on the activist and political/cultural overlaps of anarchism and punk. But even here, more than failing to be proper culture, anarchist punk also apparently fails to satisfy Cohn’s personal definition of proper anarchism, suggesting that the growth of ‘anti-organizational’ varieties of anarchism such as ’primitivism and insurrectionary anarchy’ is the result of (or the fault of) punk (2014, p. 388). As punks, we don’t really care if you don’t like our music, but to dismiss punk-associated anarchists en masse is a much more serious assertion to make. But it occurs fairly frequently. For example, in October 2021, a video essay about punk on the Anarchism Research Group’s Facebook page provoked this comment: ‘Bombs no[t] punk. Punk weaken[s] anarchism, there are no more names like S Christie, Nestor Machno [sic], G Princip, F Kaplan, Luigi Lucheni’ (Luska, 2021). Maybe we shouldn’t take an internet rant too seriously, but the underlying argument is the same as Cohn’s – that punk is not ‘proper anarchism’. Which isn’t to say that the criticism is by any means a consistent one – Cohn suggests that punk leads to ‘violent’ forms of insurrectionism, but contrarily, the Facebook commenter lists assassins and militia leaders to evidence his idea of the ‘real’ anarchism that punk lacks.

And actually, many of these sorts of figures have, in fact, been referenced in the names of punk bands, including Czolgoz (from the US, named after Leon Czolgoz, assassin of US President McKinley), Louis Lingg and the Bombs (from France, named after one of the Haymarket martyrs), and Durutti Column (from the UK, referencing the anarchist militia unit of the Spanish Civil War and Revolution, albeit while misspelling ‘Durruti’). Other bands have referenced classical anarchist luminaries in their music and imagery, to take just two examples, the 2012 song ‘Mutual Aid’ by UK ska-punk band Faintest Idea along with a T-shirt featuring the face and beard of Peter Kropotkin himself, or the T-shirt produced by 2000s US hardcore band Verse featuring Emma Goldman’s famously stern expression.

But, despite these punk nods to canonical anarchist ‘icons’, it can be argued that there is actually something distinctive about ‘punk anarchism’, and an iconoclastic rejection (or ignorance) of prominent historical figures and ideas is surely part of that (Donaghey, 2020). Take Crass for example, they were perhaps the first punk band to seriously invoke anarchism in their music and production processes, and their influence has been hugely significant – but even they didn’t know their Bakunin from their Smirnoff or Stolichnaya (Bidge, 2020). This sense of difference is at the root of those disparaging viewpoints, muddily expressed by the likes of Cohn and the Facebook commenter, and goes right back to the genesis of the punk/anarchist relationship. To paraphrase research by punk historian Matthew Worley from 2017, Anarchy magazine accused Crass and Poison Girls of ‘failing to recognise the need for a “collective strategy” or “revolutionary struggle”’, and of being ‘“too subjective”’ and ‘“naïve”’ Anarchy, 1982a, pp. 4-5; 1982b, p. 11, in Worley, 2017, p. 168). Nick Heath, writing for another longstanding UK-based anarchist periodical, Black Flag, complained in 2006 that the punk-inspired anarchists that emerged in Crass’s wake were ‘defined by lifestyle and ultimately a form of elitism that frowned upon the mass of the working class for its failure to act’ (Heath, 2006). Those ‘lifestylist’ complaints are drawn from another old-guard (ex-)anarchist, Murray Bookchin, whose polemical book detailing the supposedly ‘unbridgeable chasm’ between social anarchism and ‘Lifestyle Anarchism’ has been repeatedly repurposed as an attack on punk since its publication in 1995 (even though Bookchin himself clearly had other targets in mind).

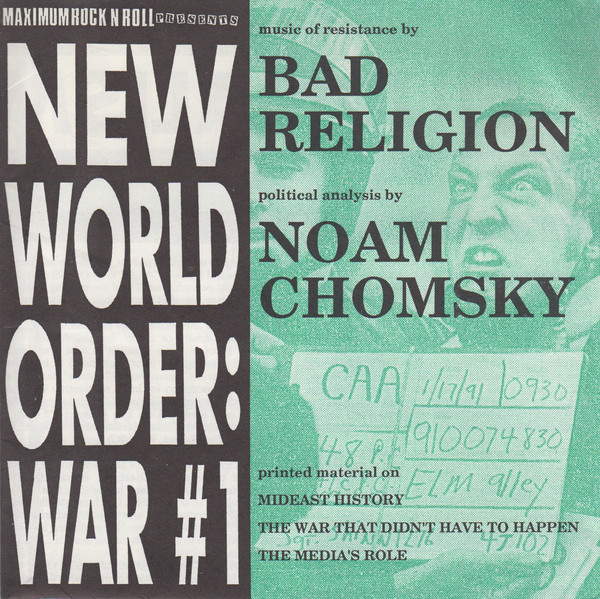

Thankfully, this anarchist hostility to punk is far from ubiquitous. Upon hearing the Sex Pistols’ ‘Anarchy in the UK’ (1976) for the first time, stalwart anarcho-syndicalist Albert Meltzer apparently thought it was ‘bloody good’ (in Nawrocki, 2012, p. 64). Noam Chomsky, perhaps the foremost celebrity anarchist of the last 50 years, even provided a spoken word essay for the B-side of Bad Religion’s New World Order EP on the MaximumRockNRoll label in 1991. But, even here the linkage is less solid than it appears. Reflecting on the Bad Religion EP twenty years later, Chomsky recalled that he ‘couldn’t make head or tail out of [Bad Religion’s] anti-war song’ and had to consult a friend’s fourteen-year-old daughter to decipher what it was all about (Fine, 2011). He adds a telling comment, however, noting that ‘for years, the main thing that people want[ed] signed [at his public talks], all over the world, was that record’. Chomsky might not understand punk, but his cheerful involvement with it has gained him plenty of adherents (and that point goes for anarchist political philosophy as a whole).

So, despite its prominence, the punk/anarchist intertwinement has been repeatedly underappreciated, either through taken-for-grantedness, bemused misunderstanding, or outright hostility. Reams upon reams have been written about punk, certainly, but the tensions and nuances that are generated in the rubbing together of punk and anarchism have not often been the focus of sustained analysis. The combination of these two messy, amorphous entities is inevitably complicated, irreducible, the source of endless arguments – and that’s exactly as it should be! In the last ten or fifteen years, things have started to change. More and more anarchist activists and punk participants have found themselves with the resources to write and publish things that resonate with their lived experience (as opposed to the detached musings of expert academicians). Comrades associated with the Punk Scholars Network have had a leading hand in this, and the internationalism of their Global Punk book series is an inspiration – even if their corporate/academic publishing avenue means the books are a bit on the pricey side (see: Bestley et al., 2019; Grimes and Dines, 2020; Bestley et al., 2021; Rodríguez-Ulloa et al., 2021; Grimes et al., 2021). Across the fields of cultural history, sociology and anthropology, numerous others have been influential in their serious appreciation of the relationships between anarchism and punk – there are too many to list here, but you’ll see their names peppered throughout the references in the chapters in the Anarchism and Punk book project series (and, of course, they’ve also written some of those chapters!). This kind of critical reflection on punk and anarchism hasn’t been limited to the shelves of anarchist bookshops, either. Activist groups like Class War in the UK and CrimethInc. in the US have offered powerful self-critiques of their own ‘punk anarchist’ politics, most notably in their publications of 1997 and 2009 respectively, and CrimethInc. have continued this critical self-interrogation in the foreword to the first book in the Anarchism and Punk book project series too. It is this tradition of auto-critique and self-reflection that we tap into with the extensive collection of chapters in this Smash The System! book.

We’ve also been keen to see the anarchist production politics of punk put into practice in the publication of these books. Active Distribution are ideal comrades in that regard – they congealed into existence in the Venn diagram overlap of punk and anarchism, starting out as a bootleg tape distro, before shifting into anarchist pamphlets and cheap books. Over the last 30 years or more they have consistently kept prices to an absolute minimum, partly from a punk distaste for profiting from cultural production, and partly from a practical concern to make their literature affordable for punks, and thereby to have a politicising impact.

Even the most culturally stunted anarcho-sceptics out there will have a hard time dismissing the depth, spread and significance of the punk/anarchist relationship in light of the richly informative and critically astute chapters we present in this book, Smash The System! Punk Anarchism as a Culture of Resistance – and that point will be hammered home across several volumes in the series. But, for those of you nodding your head along with us just now, don’t feel too smug. These chapters, and the series as a whole, should challenge your assumptions about the relationships between anarchism and punk. By looking at the experiences of our anarchist punk comrades around the world we get a sense of the diversity and resilience of these cultures of resistance (often generating head-scratching complexities and compromises along the way), but we also get an insight into the core essence that cuts across the experiences of punk anarchists, wherever they are in space and time.

Smash The System! Punk Anarchism as a Culture of Resistance, is edited by Jim Donaghey, Will Boisseau and Caroline Kaltefleiter, and published by Active Distribution in 2022.

Visit our website for more details: anarchismandpunk.noblogs.org

References

Anarchy. (1982a). Crass. Anarchy, 34, 4-5.

Anarchy. (1982b). Strength Through @! Anarchy, 34, 10-11.

Bad Religion and Chomsky, N. (1991). New World Order: War #1. MaximumRockNRoll.

Bestley, R., Dines, M., Gordon, A., and Guerra, P. (eds). (2019). The Punk Reader: Research Transmissions from the Local and the Global. Bristol: Intellect

Bestley, R., Dines, M., Guerra, P., and Gordon, A. (eds). (2021). Trans-Global Punk Scenes: The Punk Reader Vol. 2. Bristol: Intellect.

Bidge, D. (2019). Bakunin Brand Vodka: anarchism in early punk 1976-1980. Croatia: Active Distribution.

Bookchin, M. (1995). Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism. An unbridgeable chasm. Edinburgh: AK Press.

Class War. (1997, summer). The second coming: an open letter to revolutionaries. Class War, 73, 3-9. Available at https://archive.org/details/class_war_73/page/n7/mode/2up

Cohn, J. (2014). Underground Passages: anarchist resistance culture 1948-2011. Oakland, CA: AK Press.

CrimethInc. Ex-Workers’ Collective. (2009, spring). Music as a Weapon: The Contentious Symbiosis of Punk Rock and Anarchism. Rolling Thunder: an anarchist journal of dangerous living, 7, 69-74. Available at https://cdn.crimethinc.com/assets/journals/rolling-thunder-7-spring-2009/rolling-thunder-7-spring-2009_screen_two_page_view.pdf

Donaghey, J. (2020). The ‘punk anarchisms’ of Class War and CrimethInc. Journal of Political Ideologies, 25(2), 113-138.

Faintest Idea. (2012). Mutual Aid. The Voice of Treason. TNS Records.

Fine, D. (dir.). (2011, March 8). Noam Chomsky on Celebrity and Punk Rock [Jeff Jetton interviews Noam Chomsky for BrightestYoungThings.com]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ujsMGiMRynI

Grimes, M. and Dines, M. (eds). (2020). Punk Now!! Contemporary Perspectives on Punk. Bristol: Intellect.

Grimes, M., Bestley, R., Dines, M., and Guerra, P. (eds). (2021). Punk Identities, Punk Utopias: Global Punk and Media. Bristol: Intellect

Heath, N. (2006). The UK anarchist movement – Looking back and forward. Posted to libcom.org by ‘Steven’ (2006, November 15) [originally written for a 2006 issue of Black Flag]. Retrieved from http://libcom.org/library/the-uk-anarchist-movement-looking-back-and-forward

Luska, A. (2021, October 20). Comment on #Anarchism220 video on punk by Jim Donaghey. Anarchism Research Group Facebook page. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/arglboro

Nawrocki, N. (2012). From Rhythm Activism to Bakunin’s Bum: Reflections of an unrepentant anarchist violinist on ‘anarchist music’. In D. O’Guérin (ed.). Arena Three: Anarchism in music (pp. 60-70). Hastings: ChristieBooks.

Participants in the CrimethInc. Ex-Workers’ Collective. (2022). Punk – dangerous utopia. In J. Donaghey, W. Boisseau and C. Kaltefleiter (eds). Smash the System! Punk Anarchism as a Culture of Resistance (pp. i-xx). Karlovac, Croatia: Active Distribution.

Propagandhi. (2005). A Speculative Fiction. Potemkin City Limits. Fat Wreck Chords.

Rodríguez-Ulloa, O., Quijano, R., and Greene, S. (eds). (2021). PUNK! Las Américas Edition. Bristol: Intellect.

Sex Pistols. (1976). Anarchy in the U.K. EMI.

SOCAN. Past Winners webpage. Available at https://www.socansongwritingprize.ca/past-winners/

Ward, C. (1973). Anarchy in Action. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Worley, M. (2017). No Future: Punk, Politics and British Youth culture, 1976-1984. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.