By Nathan Jun and Jane Barclay

26th March 2018

Critics of anarchism have long maintained that anarchy is unrealizable in practice because hierarchical institutions such as the State are in some sense necessary and inevitable. This implies not only that these institutions will endure indefinitely in the future but also, and perhaps more significantly, that they have been an ineradicable feature of organized human societies from the very beginning. The latter claim is, of course, a descriptive generalization about the structure of human societies – in this case in the past – and, for this reason, falls squarely within the realm of anthropology. Although said generalization, if true, would scarcely constitute a decisive refutation of anarchism by itself, it goes without saying that the absence of any known societies that reflect, or at least approximate, anarchist principles could conceivably bolster the case against anarchism’s future practicability. Anthropology is singularly well-equipped to assess generalizations of this sort, which is why it is such an integral (if underrepresented and underappreciated) discipline within the fold of anarchist studies. This, in turn, explains why Harold Barclay has long been, and will always remain, a figure of towering significance among scholars of anarchism.

Alongside Pierre Clastres, Brian Morris, David Graeber, and other anarchist (or anarchist-inspired) anthropologists, Barclay made a powerful case that life without government (and hierarchy more generally) is possible for human beings in the future precisely because it was possible – indeed, common – for human beings in the past. As he notes in the introduction to his magisterial study People Without Government (1982):

Over the past several generations, anthropologists, through their ethnographic research, have documented innumerable stateless and governmentless societies throughout the world and throughout time. And even the devotees of Marx point to these as indicators of some earlier stateless stage of human cultural evolution. Nevertheless there is some considerable reluctance to define these societies as anarchies. Even amongst anthropologists there are those so imbued with their own cultural traditions that they will go to any lengths to avoid recognising these systems for what they are. Because they believe social order can exist only where there is government and law, they stretch the meanings of these terms to cover what is clearly not government at all … One task of this book, then, is to present examples of anarchy. Thereby we will demonstrate that there are human societies which fit the criteria of anarchy and should be recognised for what they are. I will [also] be suggesting that anarchy is by no means unusual; that it is a perfectly common form of polity or political organisation. Not only is it common, but it is probably the oldest type of polity and one which has characterised most of human history.[1]

In subsequent works such as Culture and Anarchism (1997), Barclay belied the abovementioned criticisms even further by bringing his copious expertise to bear on the question of “what a future anarchist society would be like” as well as how such a society might be brought about.[2] Never one to settle for purely abstract or theoretical speculation, Barclay firmly grounded these analyses in evidence, consistently employing the best practices of the empirical social sciences.

Although Barclay died as he lived – that is to say, as an anarchist resolutely committed to the ideal of anarchism – he eventually concluded that said ideal was unlikely to be realized in practice. This view, which Barclay referred to as “anarcho-cynicalism,”[3] was never motivated by the notion that anarchism is inherently unrealistic or impracticable so much as by a sober, even despairing, reflection on the pervasiveness and seeming intractability of oppressive, hierarchical institutions around the globe. Far from being genuinely cynical, however, such a view is essentially of a piece with Camus’ existentialism in its insistence on fidelity to an ideal even in the face of inevitable failure.

Lest we reduce Harold Barclay to his contributions to anarchist studies – however groundbreaking – we do well to recognize and honor who he was as a person. While it is beyond my or anyone else’s ability to pay adequate tribute to him in this respect, we are nonetheless obligated to try, lest our comrade be denied the place he so richly deserves in our memories. To this end, I would like to conclude with a brief obituary written by Harold’s wife Jane, who has graciously given her permission to share it with the readers of this blog.

—

Harold Barton Barclay

Born: January 3, 1924

Died: December 20, 2017

Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, University of Alberta

Harold Barclay arrived in Edmonton in the fall of 1966 to join the newly formed Department of Anthropology at the University of Alberta, where he became Full Professor in 1971 and Emeritus in 1989.

Harold was born in Newton, Massachusetts, the son of Mabel Barton Barclay, a teacher, and Harold G. Barclay, an automobile electrician. He spent much of his young life working and living on his grandfather’s farm in a Boston suburb. Farm work sparked an interest in agriculture and, in 1943, he received a diploma in Animal Husbandry from Stockbridge School of Agriculture in Amherst, Massachusetts.

A committed peace activist, Harold was a conscientious objector during World War II and spent two years in so-called Civilian Public Service, mostly in forestry camps in Oregon. After the war he had various jobs – as lumberyard worker, Safeway clerk, restaurant busboy, farm and ranch hand. For a short period he was also a rural school teacher in Wyoming, where he became an experienced horseback rider.

On reading Ruth Benedict’s Patterns of Culture he was “converted” to anthropology and pursued that field at Boston University, receiving a Bachelor of Arts with Distinction in 1952. On August 26, 1953, he married fellow student Jane E. Lepore, and a week later they went off to Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, where he received his Master of Arts (1954) and Ph.D. (1961) in Anthropology, with a minor in Rural Sociology.

In 1956 Harold and Jane travelled to Egypt where he assumed his first teaching position at the American University in Cairo. Soon after their arrival the “Suez War” broke out – one of many adventures during their time in North Africa. While at AUC he undertook unofficial field work in a Giza Village, later published as “A Study in an Egyptian Village Community” in Studies in Islam (1966).

His doctoral dissertation was the result of an ethnographic investigation of a village in suburban Khartoum (1959-1960). He was the first anthropologist to undertake research among Arabs of the Northern Nilotic Sudan. This was published as Buurri al Lamaab: A Suburban Village in the Sudan (1964). Following his four years in the Middle East, Harold taught at Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois (1960-1963) and at the University of Oregon in Eugene (1963-1966). He also held visiting positions at the University of Texas at Austin (1965) and the University of California at Berkeley (1966).

In 1966 general disgust with the Vietnam War led him to accept a new position at the University of Alberta. While there he studied a Lebanese immigrant community which at the time included many Muslim Lebanese mink farmers. He also researched a conservative Mennonite congregation. In a return visit to the Middle East (1971-1972) he engaged in an ethnographic study in Tunisia and explored other areas of North Africa. In the 1980s Harold and Jane revisited the villages in Egypt and the Sudan where they received a warm welcome from families they had known. Much had changed in the interim, some old friends gone, but many aspects of village life remained the same (except that they now had electrical connection and television and a few more cars).

Harold’s interests in anthropology ranged from agriculture, peasant societies and religion to political organization. He was a firm believer in the unity of anthropology and saw the discipline as both science and humanity with more emphasis on the latter. Over his lifetime he traveled widely in the Americas and abroad, always interested in people and places and the natural world. He was often amused to find, in local museums, many “historic” implements, such as a walking plow, which he had learned to use as a youth and which were still in use in much of the world.

He enjoyed living in Edmonton in Alberta, Canada where in retirement he began research on his United Empire Loyalist Ancestors. His father was born in Shelburne, Nova Scotia and was a great grandson of one of the founders (1783) given a land grant there. He also enjoyed his students, frequently inviting them to his home. Those in his Middle East classes were usually treated to a cultural evening introducing them to the food, music and informal tales from that part of the world.

In 1997 he and Jane moved to more climate-friendly Vernon, British Columbia where he was active with various discussion groups, sometimes lecturing for local organizations, and serving as a member of the advisory Committee of Okanagan University College. He continued to research and write and to support many humanitarian and anti-authoritarian causes.

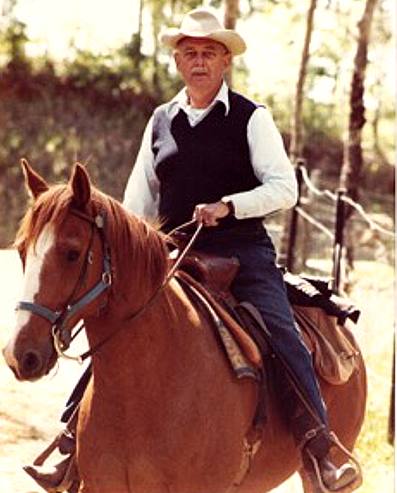

Riding horseback on country trails, along with vegetable gardening, were his favorite forms of recreation. He rode well into his 80s and his horse, Coral, was a beloved companion for thirty years. His lifetime of interest in, and study of, all things relating to the horse and its interconnectedness to human culture led to his book The Role of the Horse in Man’s Culture (1980).

Over time a series of strokes (TIAs) led to his living in a care home his last four years. He had a long and eventful life always pursuing knowledge and ideas and sharing them. Most of all he was ever concerned with the human condition and with the need for freedom, equality, and justice for all peoples.

He was the author of 10 books and countless articles.

He is survived by his wife, Jane, of Vernon, British Columbia; his son, Alan, of Federal Way Washington; his daughter, Alison, of Halifax, Nova Scotia; his sister, Frances Oxton, of Silverdale, Washington; and his nieces and nephews.

—

In solidarity with our fallen comrade and those who survive him, may he rest in power!

[1] Harold Barclay, People Without Government (London: Kahn and Averill, 1982), pp. 11-12.

[2] Harold Barclay, Culture and Anarchism (London: Freedom Press, 1997), pp. 9-10.

[3] See his Longing for Arcadia: Memoirs of an Anarcho-Cynicalist (Victoria, BC: Trafford, 2005).