by Russ Skelchy

1st May 2019

On 28 January 2019 I woke up in Manila to find an urgent text message from my sister in the US. It read: “Everything ok over there? Heard about a bombing.” Slightly confused, I got out of bed and switched on one of the local Philippine television stations. Scrolling through the channels I saw an infomercial, a basketball game, and cartoons. No news of a bombing. In fact, no news at all. About fifteen minutes later, a news broadcast finally interrupted to announce in Tagalog language that two bombs had exploded in the city of Jolo at the Cathedral of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. After sorting through the wreckage and locating the bodies of the twenty-two victims, the national police announced a few hours later that they were searching for suspects in the province of Sulu, where Jolo is located. The statement seemed like more of a formality and lacked urgency. The national police, it appeared, were as mystified as everyone else about the cause of the bombing.

In the news conference, police announced that they believed the attacks against the Catholic church to be the work of the Islamic State-inspired group Abu Sayyaf, a designated terrorist group that has engaged in armed conflict against the government since 1991. Although no actual evidence implicating Abu Sayyaf members was presented, officials used the accusations as a pretext to wage an “all-out war”, as Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte termed it, against the Abu Sayyaf.[i] The predominantly Muslim province of Sulu is known for over four centuries of armed resistance to foreign rule against the Spanish, United States, Japanese and Filipinos. Although it is unclear if the Jolo church bombing had any connection to the current movement, the government’s response to the bombing highlighted wider objectives of the wars Duterte has waged on terror and drugs. This article will briefly introduce these wars and examine responses by Filipino people I have interviewed in musician communities and organizations during fieldwork over the last few months.

War on Terror

Since taking office in May 2016, Duterte has actively pursued his “wars.” Although the wars on drugs and terror often are framed separately, the imperatives of the two interweave to extend Duterte’s authoritarian rule. In broadcasts of his speeches, Duterte is known for his blunt, accusatory statements and straight-forward demeanor. I find myself occasionally tuning into his talks for, among other reasons, the amusement of listening to him haphazardly insert English-language profanities into otherwise lackluster talks delivered in monotone deep-voice. Duterte’s smug sense of humor and informality, however, appeals to many Filipinos. His public persona, in this sense, has drawn comparison to current US president Donald J. Trump.

A key objective of Duterte’s war on terror is to solidify political control over the predominantly Muslim areas of the southern Philippines. In response to decades, if not centuries, of political unrest in the region, provinces on the west coast of Mindanao and Sulu in 2012 were designated as the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). This designation ostensibly expanded local control over the region’s government. In early January 2019, just three days before the Jolo bombing, a referendum was held in Muslim Mindanao calling for the establishment of a new designation, the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), following up on the earlier Bangsamoro Law, which passed with the Duterte regime’s support in July 2018. It is important to locate the word “Bangsamoro” historically – it combines two words: bangsa from the Malay word for nation, and Moro, a term used by the Spanish for the ethnolinguistic group of Islamized people of the southern Philippines. Culturally and religiously, Bangsamoro connects the region with other Muslim people in Indonesia, Borneo and peninsular Malaysia.

Duterte’s support for the establishment of BARMM rests primarily on the incorporation of leaders from the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), an Islamic separatist organization in the southern Philippines, into the realm of national parliamentary politics. Theoretically, the law allows the region greater control over its fiscal economy and the revenue from its vast natural resources and will help to fund the building of local infrastructure. Opponents argue that in practice BARMM does little to address structural issues of poverty, corruption and wealth inequality. Critics suggest that “imperial Manila” elites will never allow for true decentralization and “genuine fulfillment of the Moro people’s right to self-determination;” instead they will rely on “traditional local politicians to be their lackeys.”[ii] The assumption is that economic development and political reform will continue to reap profits for the distant Manila elite. From this perspective, there is little to differentiate BARMM from previous attempts to create an autonomous region in the southern Philippines. Furthermore, the federal government has extended martial law in the BARMM city of Marawi through 2019. Martial law was initially imposed in May 2017 after a protracted armed conflict between Philippine government forces and rebel fighters affiliated with Islamic State, which included members of Abu Sayyaf and other local groups.

In late March 2019 Duterte confidently proclaimed that the government was winning the war on terror stating, “With your untiring loyalty to the flag … I have no doubt that we will win the war against those who seek to sow terror in our communities, especially in the countryside.”[iii] Duterte added that he would like to see an end to this phase of the war against Philippine terrorist groups such as Abu Sayyaf, communist rebels and drug traffickers in “about three years.”[iv] Duterte’s regime, however, has targeted far more than these specific groups. There have been many instances where journalists, teachers, activists and others who have criticized Duterte’s actions have been subjected to public humiliation, silencing, arrest or killing.[v]

Responses to the Drug War

Similar to the war on terror, Duterte’s war on illegal drugs and drug traffickers has been a major issue in the Philippines. Many of his supporters aver that it has made the Philippines safer by rooting out criminal behavior. Others attest that the name itself is a misnomer, instead calling it a “war against the poor” since the urban poor have largely been the targets of extrajudicial killings carried out by police.[vi] At a recent local concert, Emman, a Manila punk record label owner, told me, “This war on drugs is a big hoax … there are no big drug lords getting caught … They’re just trying to do this to take [advantage of] people’s fear … to establish order. If you [think] the war on drugs is making the Philippines safer, that’s a big joke. It hasn’t made the country safer.”

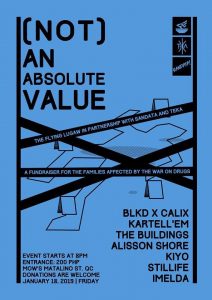

Philippine National Police (PNP) statistics put the total number of people killed in the war on drugs so far at around 7,000 since 1 July 2016.[vii] Others suggest that the actual number is closer to 30,000 killed. To address this discrepancy and other disinformation circulating about the war on drugs, local groups have formed to conduct independent research into the extrajudicial killings. One such group, Sandata!, consists of researchers, development workers, photojournalists and artists based in the Manila area. Sandata! formed in 2017 as part of a project grant under the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism with the intent of translating investigative pieces written about the drug war into a hip-hop concept album. The group has since expanded its scope to include policy work, community outreach, public talks domestically and internationally, and fundraising to support families affected by the Philippine drug war. As Abbey Pangilinan, a Sandata! researcher, explained to me,

“We started to think of ways to communicate better [with the public] since no one really is [interested in] looking at our Powerpoint presentations [she laughed], so [local Manila hip-hop artists, BLKD and Calix] began brainstorming on how to use music to communicate stories about the war on drugs. That started it and [since then] we’ve been working with family’s affected. We’ve realized that we can help them just by telling their stories … especially the magnitude of losing a breadwinner in the family.”

Mixakaela Villalon, a writer and artist working with Sandata! on the musical side of the project, discussed the connection between researchers, artists and the communities affected by the killings.

“The idea is to get the information out to people, particularly to the communities affected. We want to give them back the information that they’re giving us because they’re not the type of people who would be reading newspapers, especially in English. The [researchers] provide us [musicians] data, the rappers write, and I try to like tweak or edit when I see like a line that can be pushed to the limit. I encourage them to edit the lines and I’m the person who stands between the research and the artists. I try to get them to communicate to each other.”

Abbey and Mix described how the effects of the war have been felt by low-income families who, in many cases, have become poorer due to the loss of a father or brother. Children are taken out of school and further stress in placed on the remaining parent (or other family members) who, in many cases, must take on additional jobs to support the family. To share these types of stories, Sandata! have partnered with local musicians in various genres, including hip-hop, punk, indie rock and heavy metal, to organize benefit concerts for families affected by the war on drugs and to share information widely about the killings.

“We want to … start talking with people in the [rural] provinces. Our goal [in the beginning] was to research the effects of the Philippine drug war, now it [has shifted] to communicate that research on the magnitude [of the drug war] and how it affects families. Often people only see broad strokes, they see 28,000 dead, but they don’t see how deeply it affects the social pattern. What are the effects of a poor family losing a father? The music came [afterward], because that’s the point of doing research. What’s the point if the communities can’t access it? We thought it would be more powerful for them … to hear the stories … told through music.”

Part of what Abbey and Sandata! have done is to provide important information on the ground about the drug war. For instance, Abbey told me that through conducting interviews with residents in one part of Manila, she found out there had been nearly 900 killings in that area alone. Rather than relying on aggregate numbers provided by the police and other federal agencies, Sandata!’s work has allowed for a more accurate mapping of where the killings have been concentrated and who they have targeted.

Not surprisingly, musicians and artists have been at the forefront of resistance to Duterte’s wars. For instance, two Manila rappers, BLKD, whose stylized name derives from the Tagalog word balakid (obstacle, barrier), and Calix, are active contributors to Sandata! Both rappers are quite popular in the local hip-hop scene and have made a name for themselves through Manila’s Fliptop Battle League, a showcase for some of the Philippines’ best hip-hop talent. Since joining Sandata!, BLKD and Calix have performed at several benefit concerts and are currently working on a concept album titled Kolateral: Buelo (Collateral: Buzz), which explores the machinery and bureaucracy behind Duterte’s war on drugs. Themes for the album draw directly from government memoranda, executive orders and “mission orders,” to expose the government organizations who have carried out Duterte’s decrees. “Makinarya” (Machinery), a promotional track that BLKD and Calix have recently released, begins with a sound clip from a Duterte speech encouraging police to kill suspected drug dealers openly in the streets. The song’s initial beat is inspired by the sound of police knocking on doors as they search neighborhoods for suspected drug users. The lyrics to “Makinarya” explore how Duterte’s words are turned into bullets, insisting that although Duterte may not be the one personally pulling the trigger, he is responsible for the thousands killed. In subsequent stanzas, BLKD and Calix explore the perspective of government employees who translate the Duterte regime’s ideas about the drug war into actual state policy. They describe how these orders travel through the government bureaucracy culminating in orders given to police, local government officials and barangay (neighborhood) leaders to eliminate suspected drug users and sellers.[viii]

[Listen to “Makinarya” (Machinery) here—https://oplankolateral.bandcamp.com/releases]

Future Constrictions

Rodrigo Duterte assumed power in 2016 following a campaign that promised to reduce crime. His twin wars on drugs and terror have been a pretext to consolidate his own power and constrict dissent. The significant number of appointments of military men to seats of power in the government have many Filipinos anticipating the expansion of authoritarian rule and the imposition of de facto martial law in the coming years.[ix] In terms of the drug war, many of the people I have spoken with in Manila personally know someone who has been killed in the war. Some have described how the fear of police raids has gripped their barangay (neighborhood) and have caused them to stop socializing openly in streets and public areas. Instead, many have chosen to socialize inside their homes or concealed areas, such as backyards. The effects of this constriction of free space, literally and metaphorically, is an aspect of Duterte’s wars that requires further exploration. As Filipinos continue to negotiate this current political reality, questions about how they will stop the extrajudicial killings, and not (further) relinquish their freedoms, are central to how they will move forward. As BLKD astutely observes in the song “Makinarya” (Machinery),

“Para sa kaayusan, para sa kaunlaran, para sa kapayapaan, ano ba naman ang kamatayan?”

(For order, for development, for peace, what is death?)

References

[i] Unattributed (2019), ‘Jolo blast death toll climbs to 22: military’, ABS-CBN News, 1 February, https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/02/01/19/jolo-blast-death-toll-climbs-to-22-military

[ii] Janess Ann J. Ellao (2019), ‘Can Bangsamoro Autonomous region bring genuine peace to Moro people?’ Bulatlat, 28 February, https://www.bulatlat.com/2019/02/28/can-bangsamoro-autonomous-region-bring-genuine-peace-to-moro-people/

[iii] Genalyn Kabiling (2019), ‘Duterte confident of winning against terror groups, drug traffickers’, Manila Bulletin, 22 March, https://news.mb.com.ph/2019/03/22/duterte-confident-of-winning-against-terror-groups-drug-traffickers/

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Eijas Ariffin (2018), ‘Duterte’s war on activists’, The ASEAN Post, 22 June, https://theaseanpost.com/article/dutertes-war-activists

Speech given by Christina Palabay (Karapatan) 17 March 2019, San Francisco, CA USA

[vi] Patrick Quintos (2018), ‘Poor Filipinos most vulnerable in Duterte’s drug war: study’, ABS-CBN News, 25 June, https://news.abs-cbn.com/focus/06/25/18/poor-filipinos-most-vulnerable-in-dutertes-drug-war-study

[vii] Michael Bueza (2017), ‘IN NUMBERS: The Philippines’ “war on drugs”’, Rappler, 23 April, https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/145814-numbers-statistics-philippines-war-drugs

[viii] From “Sandata! Art and Data Against Disinformation and the Philippine War on Drugs” (February 2019)

[ix] Karl Kaufman (2019), ‘“De facto martial law” feared amid Duterte’s plan to appoint more military men to gov’t’, MSN News, 4 October, https://www.msn.com/en-ph/news/world/de-facto-martial-law-feared-amid-dutertes-plan-to-appoint-more-military-men-to-govt/ar-BBVMv0k

Pia Ranada (2018), ‘LIST: Duterte’s top military, police appointees’, Rappler, 15 December, https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/218702-list-duterte-top-military-police-appointees-yearend-2018