by Mustapha Mond

4th February 2021

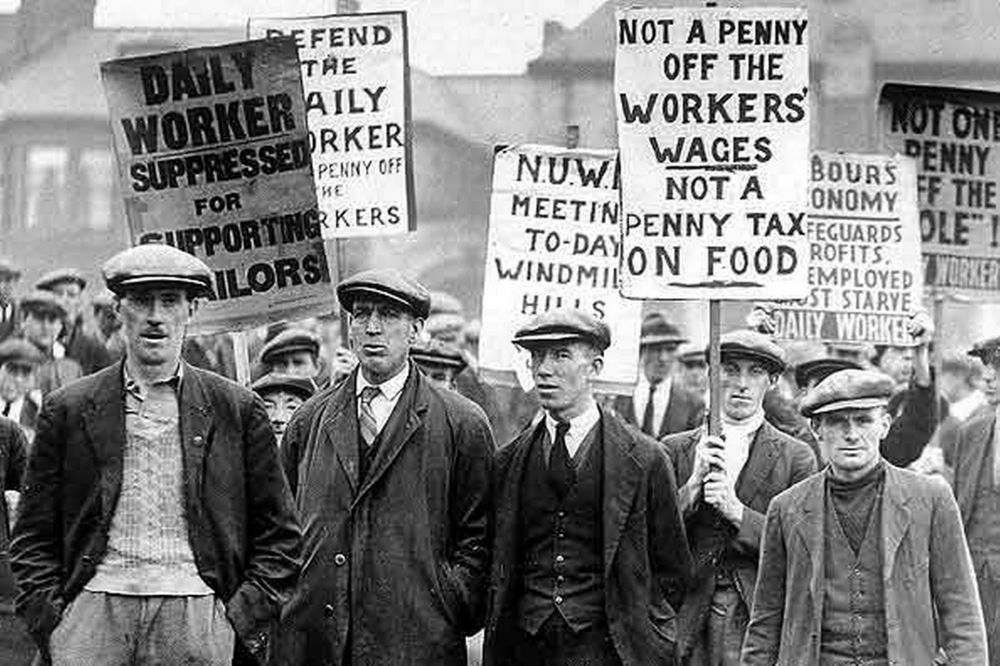

Ever since Karl Marx outlined his analysis of capitalism and the inevitable socialist society that would replace it, history has observed countless experiments in the name of “socialism” or “communism” which have had drastically varying degrees of success, these have ranged from anarchist interpretations to outright totalitarian bastardisations of Marxist thought. One such experiment which appears to have been long forgotten and stamped into tragic irrelevance is that of syndicalism: the radical labour movement that advocates workers’ self-management, organisation, direct action and unionisation in order to abolish the capitalist order. As Rudolf Rocker explained in 1938, the history of syndicalism predates Marxism and draws its temporal roots back to the early 1800s, with the birth of the modern labour movement in response to the absolute destitution and misery which the industrial revolution had levied on the working masses of Britain. The movement has a tumultuous, indeed horrifically violent, history and was an overt exposition of one of the primary drivers of history: class struggle. Countless now-forgotten working class people lost their lives during the fight for better conditions and the right of working people to assemble and unionise. Poverty itself was criminalised and 1812 legislation, the so-called ‘Destruction of Stocking Frames, etc. Act’ imposed capital punishment for “luddism” – the destruction of capitalist machinery during protest. Eighteen workers were hanged at York Castle in 1813 and thousands were deported to Australian penal colonies. Many more died during brutal state repression of mass meetings, such as the 400 proletarians killed in Petersfield in 1819. Such were the events that first gave rise to syndicalism.

Marxist and early socialist literature informed the modern labour movement and gave it a revolutionary consciousness and purpose as opposed to earlier goals, such as that of Chartism, which simply aimed at political reform rather than the cessation of capitalism. The result of this synthesis, syndicalism, has had varying definitions throughout history but can be summarised thusly: the establishment of worker-owned and worker-controlled organisations or unions, proletarian ownership of the workplace, advancement of workers’ demands through strikes or other direct action and use of the general strike as the ultimate revolutionary armament, through which capitalism would be overthrown. Victor Griffuelhes described this final, ultimate, revolutionary general strike as “the curtain drop on a tired old scene of several centuries, and the curtain raising on another”. The most popular form that this revolutionary labour movement took was that of anarcho-syndicalism, with the writings of Mikhail Bakunin, Rudolf Rocker and Georges Sorel forming an informal theoretical framework for it. It thus became commonly assumed that syndicalism was intrinsically linked to anarchism: that state and corporation were two sides of the same oppressive bourgeoisie coin, and both had to be done away with, in order for co-operative, worker-controlled, democratic systems to arise. However, the concept of syndicalism is not dependent on the absence of a state; this was simply the most popular historical form the philosophy took.

Here is where I would like to posit the inevitable question: could syndicalism have been the cure for our malady? Could we have abrogated this absurd and deeply malevolent capitalist world in which we now live, which appears to be edging ever closer to collapse, had we listened to Bakunin during the First International and followed a path of syndicalism? I believe this question is worth exploring. Perhaps a syndicalist society is the one which most truly conforms to the original conceptualisation of socialism by Marx, as it would necessarily entail the means of production being directly in the hands of the working classes, the proletarians, through worker co-operatives, unions, boards and committees rather than in the hands of the state through bureaucrats, autocrats, politicians and dictators. History’s “socialist” experiments have too often resulted in the exaltation of authoritarianism and a lack of direct democracy, handing the means of production to the state as so-called “public ownership” rather than directly to the people. This was one of the most successful deceptions in history and spawned a multiplicity of “socialist” nations founded on the principles of “Marxism-Leninism”. This, Stalin’s bastardisation of Marxism, lacked almost any resemblance to the original formulation.

These regimes have often failed to keep up with social development and instead remained static, which is in direct contrast with the recognition of constant change supposedly underpinning the dialectical materialist ideology that guided their existence. This doomed them to failure. It has been evident in the USSR, Cuba, China and other nations, that once a new elite had established power, there was a lack of motivation to move beyond the dictatorship of the proletariat. This eventually resulted in the creation of, as Trotsky termed it, “degenerated workers’ states”. The unwillingness to lend more direct control to the workers, friction between development of the means of production and advancement of society led to paradoxically renewed class antagonisms: an irreconcilable friction between workers and bureaucrats. History has shown us that the inability to resolve these antagonisms leads to a disintegration of the “socialist” state. Thus, the unmovable power structure that is the “dictatorship of the proletariat” is one that cannot withstand the forces of social development and, in response to social change, the authoritarian leadership entrenches itself further, condemning the project to decay. In reality, these states were just autocratic, centrally-planned, state-capitalist nations which opposed Western imperialism: they did not achieve socialism.

A full analysis and interrogation of history’s previous “socialist” experiments goes beyond the scope of this piece, and there were indeed both noble and abhorrent outcomes as a result of their formation. I do, however, propose that these were great tragedies, with anti-capitalist revolutionary fervour diverted toward the incorrect solutions. Hence, we are still faced with our current worldwide malady of end-game capitalism. These failures of history were due to the fact that state-monopolised property is simply Bourgeoisie property in new clothing, whether it is controlled by autocrats or, in liberal democracies, indirectly by capital. Private property has never truly been abolished and entrusted to the proletarians directly, yet this is what syndicalism would achieve. Bakunin once authoritatively explained how the state is an extension of power and acts as an oppressor just as capital does, whilst the institution of authoritarian regimes in the name of communism simply replaces the Bourgeoisie with a new elite oppressor class. His prediction that Marxism would lead to a new despotic “red bureaucracy”, more dictatorial than a capitalist system, played out through history as if prophecy. The truth is that socialism has failed in most of its trials throughout world history because the “social” within “socialism” was forgotten: power was never truly socialised to be in the hands of the masses, only abstractly or on their behalf by the state, and this has led to great atrocities in the name of proletarian liberation.

Marx was profoundly prophetic and correct in his analysis of capitalism, its exploitation, and class struggle, with the dialectically inevitable remedy of socialism as strikingly obvious today just as it was in the 1800s. However humanity has failed in its implementation of this antidote, and so our malady remains. Marx once wrote that the dictatorship of the proletariat “begins with the self-government of the commune”. That is to say such a dictatorship would be a bottom-up system of direct democracy, rather than top-down control. The contemporary theorist Richard Wolff often defines socialism as “the democratisation of the workplace”. I would argue that syndicalism on a national or international scale is the exact exposition of such an idea: the syndicalisation of society would put direct democracy in the hands of the working classes, would directly democratise the places in which they work, and would grant them the ownership of the means of production which has historically evaded them so heinously. It could be the very essence of socialism.

Mustapha Mond is a regular contributor to the blog site Malady: Politics, Philosophy and Class in the 21st Century

References

1812: 52 George 3. c.16: The Frame-Breaking Act [Internet]. The Statutes Project. 2021 [cited 16 January 2021]. Available from: https://statutes.org.uk/site/the-statutes/nineteenth-century/1812-52-geo-3-c-16-the-frame-breaking-act/

Bakunin M. God and the State. 4th ed. 1882.

Black C. Marxism, Leninism, and Soviet Communism. World Politics. 1957;9(3):401-412.

Darlington R. Syndicalism and the transition to communism. 1st ed. 2008.

Fourteen Malefactors [Internet]. English Crime and Execution Broadsides – CURIOSity Digital Collections. 2021 [cited 16 January 2021]. Available from: https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/crime-broadsides/catalog/46-990073455360203941

Guérin D. Jeunesse du socialisme libertaire. Paris: Marcel Rivière; 1959.

Marx K, Engels F. The communist manifesto. 4th ed. 1848.

Marx K. Conspectus of Bakunin’s Statism and Anarchy [Internet]. Marxists.org. 1926. Available from: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1874/04/bakunin-notes.htm

Mayer R. The dictatorship of the proletariat from Plekhanov to Lenin. Studies in East European Thought. 1993;45(4):255-280.

Petras J. Authoritarianism, democracy and the transition to socialism. Socialism and Democracy. 1985;1(1):5-27.

Poole R. ‘By the Law or the Sword’: Peterloo Revisited. History. 2006;91(302):254-276.

Rocker R. Anarcho-Syndicalism: Theory and Practice. 3rd ed. 1938.

Rogers N, Epstein J, Thompson D, Thompson D, Wilks I, Jones D. Chartism and Class Struggle. Labour / Le Travail. 1987;19:143.

Solidarity Federation. A short history of British Anarcho-syndicalism [Internet]. Solfed.org.uk. 2021. Available from: http://www.solfed.org.uk/solfed/a-short-history-of-british-anarcho-syndicalism

Trotsky L. The revolution betrayed. New York: Pioneer Publishers; 1936.

Wolff R. Start With Worker Self-Directed Enterprises [Internet]. Thenextsystem.org. 2017. Available from: https://thenextsystem.org/sites/default/files/2017-08/RickWolff.pdf