by Frans Ari Prasetyo

14th September 2020

May Day in Bandung has traditionally been a trade union-led day of action in the city, with an occupation of public space concentrated on the grand Gedung Sate building (office of the Governor of West Java) and mass demonstrations in Gasibu Plaza.

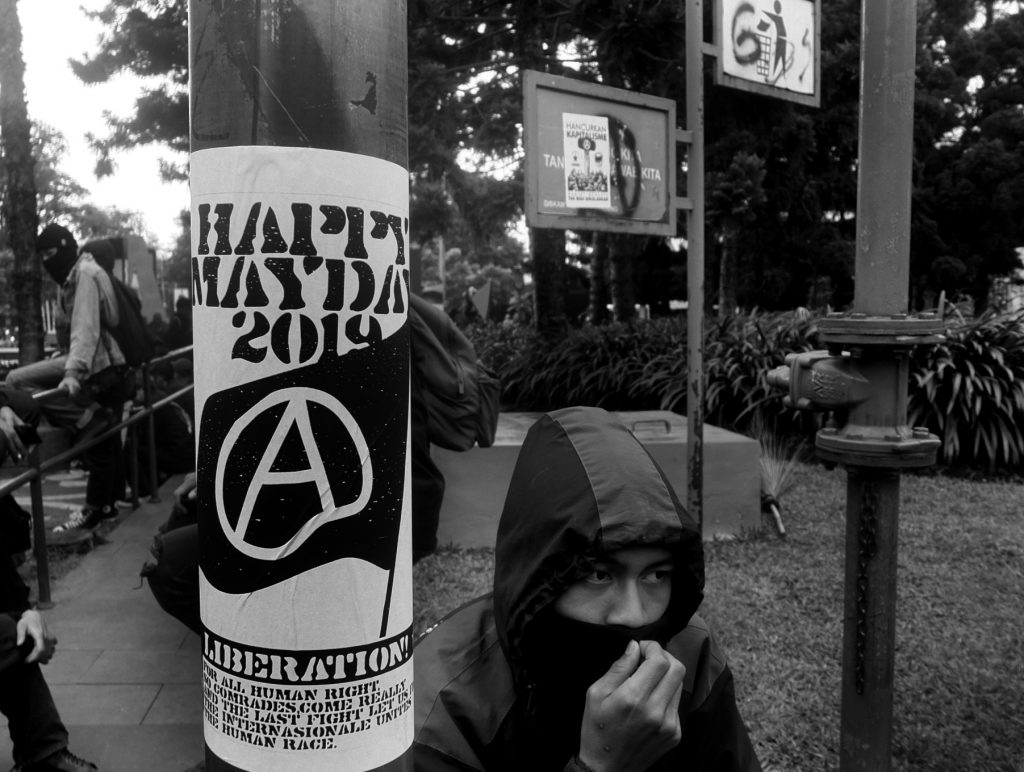

Over the last five years, the character of the May Day demonstration has shifted from the traditional pattern, with an escalating presence of ‘black bloc’ anarchist activists and wider participation from a loose alliance of supporters.

Since 2015 Cikapayang Park, in the Dago area, has been a popular gathering place for Bandung youth, transforming into a new political space during May Day. A straight road of 2km separates the park from Gedung Sate.

The traditional protest outside the office of the Governor of West Java has taken on increased sharpness under the Governorship of Ridwan Kamil (previously mayor of Bandung). Kamil oversaw the eviction of four kampungs in the city, to make way for gentrification, forcibly displacing thousands of labourers and urban poor.

In the wake of the resistance campaigns against Kamil’s gentrification policies, the May Day 2019 actions attracted large groups of hooded, black-clad protestors, amassing more-or-less spontaneously. They joined the protests, acting individually and independently, and not in affiliation with any particular organisations or trade unions, to show solidarity with the May Day demonstration.

The protesters came to target symbols of capitalism. They chanted anti-fascist slogans, waved anarchist flags and anti-capitalist banners, with slogans against eviction and ‘land grabbing’, raising issues around the right to the city, workers’ rights and human rights. Some protestors started to erect barricades.

The protests focused on a strong opposition to capitalism as the hegemonic economic and social system, emphasising solidarity with workers and the possibility of alternatives. This movement involves exploring and exposing all the hype and contradictions of the so-called gig economy, where automation’s potential for increased time away from work is subordinated to military-police and state surveillance, speed-up capital, and much else that makes for contingent work and precarious living in the city.

The demonstrators amassed from 8am, arriving one-by-one from various places in the same black garb and black masks. Beyond the connections within their own small circles, these groups of black hooded protestors did not know each other.

About 2,500 people gathered, and, like in previous May Days, I joined with the black mass, arriving at Cikapayang Park at 8:15am complete with skate helmet and a camera to document this movement. (Of course, the black outfit has everyday practicality since is hard to get dirty.)

Before marching, the amassed protestors were warned by someone wielding a megaphone not to be violent, nor to vandalise or destroy public and private facilities. Of course, during the march, there were several people graffiti-ing walls, especially on Pasupati Flyover, but private houses were not targeted.

A police officer approached me, asking ‘do you know who this group are?’ ‘I dunno’, I answered. He continued, ‘why are you wearing the black outfit?’ ‘This is my favourite colour and it’s hard to get dirty’ I said.

I asked him, ‘how come you’re wearing a black outfit too?’ ‘This is the uniform of Prabu, a special police unit’ he replied. ‘So there are a lot of police in black uniforms today?’ I pressed. The police officer didn’t answer, but asked, ‘why are you wearing a helmet?’ I returned the question, ‘why are you wearing a helmet?’ He replied that it was ‘for safety’. ‘Same here, for safety’ I nodded. ‘Safety from whom?’ asked the cop. ‘Safety from you’ I replied, and then he was gone.

At around 10am, the demonstrators moved into Surapati Street and blockaded the road. Soon after there was a clash with police towards the rear of the group in nearby Bagusrangin Street, with several demonstrators and journalists beaten with sticks and some people forcibly abducted from the narrow street. I was present in this clash. Police fired their guns, crashing their tactical car and motorcycles into the demonstrators and scattering the barricade.

This incident split the black bloc, making police arrests easier. About 300 people had already been detained by the police, including other groups who had been waiting at the Juang Monument. Demonstrators were now scattered and numbers had significantly decreased to around 700 people. They were then cornered and directed by the police to go towards another road which seemed to have been pre-prepared as a ‘kettle’. Yet most of the black bloc protests had been non-violent, and clashes with police were isolated pockets.

For about an hour, these demonstrators were left in the police kettle, unable to do anything. Meanwhile, the police brought in further reinforcements, complete with assault rifles, and they even brought in the military. The remaining crowd gathered on the Dipatiukur Street, taking turns to give speeches, and then continuing the long march along Teuku Umar Street. On the road to Teuku Umar Street, this group of demonstrators began to be chased by several police cars, dozens of police motorbikes and trucks containing dozens of soldiers.

The demonstrators were driven in the direction of Juanda Street (in the Dago area) with the police increasingly pressuring the demonstrators. The police forced the protestors to walk on the sidewalk, and they did so in an orderly manner. But while in front of Boromeous Hospital, police officers began beating up the demonstrators and arrested several people including journalists and disabled people accused of being coordinators, forcing them into police trucks.

In this chaotic situation, the demonstrators scattered and turned to run away from the police lines. But a combination of police, Brimob (tactical police unit), and the military lay in ambush, thus the repression of the demonstrators increased.

Finally the demonstrators dispersed, but not before the police managed to capture a total of 619 people in a 2km-radius swoop, randomly detaining all those who were dressed in black. Those arrested consisted of 326 adults and 293 under-18s.

At some point during their arrest, the demonstrators were publicly stripped naked and their bodies and faces were spray painted, not to mention the physical and verbal violence. Of course, this treatment of the May Day demonstrators was a violation of human rights (including imposing sentences without a civil court process), but it was also a violation of the police’s own code of ethics. The police also confiscated (robbed) smartphones, camera, laptops and wallets – none of which were returned. Eventually, at around 12 midnight, those who had been arrested were released.

The public reaction to the incident varied. The Bandung City Civil Society Coalition criticised the actions of police and the military, including arbitrary arrests without cause and carrying out punishments without trial (stripping people naked, shaving their heads, forcing them to squat down, spray painting their bodies). In addition, the police obstructed journalists from obtaining information and were criticised for involving the military in civil affairs.

The protests were a convergence of various movements of heterogeneous interests, joining together for this fight. Solidarity was demonstrated in the resistance to the repression by the police and military authorities in Indonesia. The simplicity of these protests represents the potential of the May Day movement to influence social and cultural changes in the city.

[This article is based on a presentation given at the Ethnography Lab of the University of Toronto in 2019.]

Frans Ari Prasetyo (fransariprasetyo@gmail.com) is an independent researcher and photographer who lives in Bandung, Indonesia. His interests are the evolution of urban politics, culture and sub-cultures, artists and underground activists.