by Elise Imray Papineau

8th February 2022

Grassroots activists have long been using methods of direct action to disrupt the status quo, while embodying the principles of non-hierarchy, autonomy, and participatory democracy in their own organizing structures. The Do-It-Yourself (DIY) ethos is enmeshed in grassroots activist spaces, shaping both the broader culture of those activist collectives and their specific practices of resistance. Despite its co-optation by capitalist rhetoric, DIY still holds considerable merit today as an embodied form of political praxis which rejects the establishment, elitism, consumerism and neoliberalism. In the context of mutual aid and collectivity since the start of the pandemic, however, we may prefer to talk about Do-It-Together (DIT), which highlights the interdependence – rather than the individual independence – of people within grassroots communities. The idea of Do-It-Together is a call to collective action, which overlaps with Kropotkin’s notion that humans have an innate predisposition to engage in mutual cooperation outside of governmental coercion[i], but encompasses other forms of group resistance and communal efforts beyond the definition of mutual aid.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, mutual aid initiatives around the world have increased in breadth and scale, some undertaken by informal groups of peers, and others by organized grassroots collectives. It is no surprise that grassroots, community-led projects have intensified since 2020, as more and more people have become exposed to the failures of modern capitalist institutions. In many countries worldwide, government mismanagement of the crisis has incited its residents to take care of one another. Morales describes this in his earlier AnarchistStudies.Blog article on the same topic: “Neighborhood organizations, or even organizations at the level of neighborhood communities, have developed as a way to reach where the authorities could not. In the absence of authority, anonymous people have continued to need what the state used to provide.”[ii] In this article, Morales argues that self-organization and forms of mutual support in Western countries tend only to emerge spontaneously in situations of necessity, or in times “when competition and authority have to be suspended”. At first glance, this argument seems appropriate in the Australian context, where I have been living during the pandemic, though it does not necessarily hold true in places like the UK and elsewhere in Europe where existing mutual aid networks rooted in political struggle have long preceded the COVID-19 crisis. Spontaneity and necessity may be catalysts, but still require rudimentary structures to be in place in order to facilitate their emergence. Following Morales’ article, I find myself curious to explore how much – or conversely, how little – this varies in non-Western contexts. How greatly do the cultures of collective cooperation differ in Australia from those in Southeast Asian countries like Indonesia and the Philippines, where there is both more need and more space for mutual aid initiatives?

As part of a broader research project on grassroots activism, I have been documenting the activity of collectives in Australia, Indonesia, and the Philippines over 2020-2021. My aim here is to highlight some lesser-known initiatives and situate them in their cultural contexts. This is an exploration of mutual support responses around the pandemic, but also a critical look at why and how they seem to remain more consistent in Indonesia and the Philippines, in contrast to Australia.

Mutual aid and grassroots initiatives in Australia, Indonesia, and the Philippines

We’ve seen a wide range of collectives and projects popping up across countries of the Asia Pacific engaging in grassroots solidarity work as the pandemic has exacerbated systemic inequality and disproportionately affected marginalized populations. These grassroots collectives focus on a range of issues, from housing justice and access to health services to protection from increased domestic and sexual violence. The most evident red thread across the mutual aid initiatives I have documented in Australia, Indonesia, and the Philippines, perhaps unsurprisingly, is that of food and agrarian justice. Food Not Bombs (FNB), one of the prime examples of mutual aid globally, has active chapters in all three countries which precede the pandemic – and will (almost certainly) outlast it. As FNB is already widely recognized, I will present some other examples of food and land-centered projects.

A great example of this hails from Brisbane, Australia. Growing Forward guerrilla gardens are a grassroots initiative with the dual purpose of reclaiming land and pursuing practical means of food sovereignty. Since 2020, this community of gardeners have expanded the movement with multiple sites throughout the urban sprawl of Brisbane. Growing Forward organizers frequently host working bees at each garden plot where newcomers can get involved with the movement and learn basic gardening skills. Not only do its members promote the importance of grassroots food security, but they also share a strongly anti-capitalist view and advocate for the reclaiming of urban, public space. When one of the Growing Forward garden plots was threatened by developers in late 2021, guerrilla gardeners and their comrades took to the streets to oppose the proposal and warmly suggested “composting the rich” instead. The harvests themselves are either offered directly to community members, including recently resettled refugees, or brought to venues like The Social Space, where volunteers cook up free plant-based meals for locals. The Social Space also runs a free shop where “shoplifting is encouraged”, following a similar anti-consumerist and anti-capitalist ethos. The physical space existed before the pandemic but operated at a much less significant capacity. With the collaboration of Growing Forward and other community groups – spurred by an increased interest in mutual aid – The Social Space has gained momentum.

On the island of Java, Indonesia, I spoke with a handful of feminist groups who brought up the importance of food and land justice, linking these with the struggle for women’s liberation. Solidaritas Perempuan Kinasih in Yogyakarta have not only been involved with the fight of Kulon Progo farmers against development on their land, but have also supported local agricultural workers during the pandemic, for example, by setting up virtual markets in which they can sell their produce. They also assist in bridging the digital divide by upskilling them on using tech and helping to create harvesting vlogs, an accessible way to highlight the connection between feminist ideologies, agricultural practice, and food justice. This additionally helps to spread awareness about the conditions that farmers are working in during lockdown. Other groups, including anarcho-feminist collective, Needle and Bitch, participate in a public street kitchen for informal workers, encouraging them to learn basic cooking skills on top of providing them with a meal. Beyond the immediate need to address hunger, this practice aims to break down pervasive gender roles in which only women do the cooking. These examples showcase the value of horizontal skill-sharing as part of mutual support, which fosters resilience and autonomy within communities rather than creating dynamics of dependence.

In the Philippines, where the peasantry makes up an enormous portion of the population, the plight of rural workers and land defenders is a key focal point for many grassroots collectives and organizations. One of the notable examples of resistance and mutual support that preceded the pandemic – but was amplified during this period – is the bungkalan movement. The word means to till or to cultivate crops. An activist I spoke with from Rural Women Advocates (RUWA) explained:

It’s the initiative of organized farmers and even organized urban communities. They would till vacant lots or lands that are not being filled. It started as a response to hunger. And now there are bungkalans in the city, in the urban areas where communities are being demolished, making place for casinos and hotels and malls. They would demolish the urban poor communities. It responds to their hunger now and during the pandemic, we’re in lockdown, some of the farmers are not allowed to go to the sakahan, to the farm. So, they do the bungkalan in their communities, the small bungkal so they can survive the lockdown.

Since the Philippines retains a semi-feudal system where land ownership disputes affect the majority of agricultural workers, the bungkalan movement is both political and practical. It fosters greater cooperation among the peasantry, uniting them in the struggle for grassroots-led agrarian reform, and helps to ensure food security for farmers and their families who have been left hung out to dry by their government. During the pandemic, ‘COVID gardens’ also began to pop up: these gardens offer not only a source of food, but also purposefully grow herbal plants that double as traditional medicines to help treat those who are sick.

Do-It-Together: in spite of – or in absence of – the state?

Let’s go back to the point made by Morales about mutual support and community care in Western countries being a result of necessity and emerging spontaneously rather than being an ongoing practice. I want to briefly explore how some of the values of solidarity and grassroots cooperation are reflected in each country, and draw some associations between pre-colonial vernacular in Indonesia and the Philippines with the ongoing mutual aid initiatives that some groups and individuals engage in on a consistent basis.

In countries like Indonesia and the Philippines, harsher socio-economic conditions and social unrest may lead to more unstable and polarized societies, thus increasing the demand for grassroots resistance, community organizing and collective survival strategies. On the other hand, the proliferation and consistency of mutual aid initiatives in these countries may also be attributed to the limited reach of the state. In countries like Australia, where the state has a far greater prevalence in people’s public and private lives, networks of cooperation are more often interrupted or diminished.

Australia, dubbed ‘the lucky country’ by author Donald Horne[iii], exists under the premise of widespread social and economic stability, though approximately one in ten Australians struggle to survive on income payments that are well below the poverty line. It is one of the richest countries in the world, yet it retains a much greater sense of political apathy than in the UK and North America. The pervading expression of “she’ll be right” spoken in Aussie vernacular reflects at once a sense of nonchalance as well as a childlike trust that the government and other current institutions will take care of things. Impending climate catastrophe? She’ll be right. While it is a far-reaching generalization, this expression exposes the culture of complacency that stifles grassroots movements and keeps Australia in a state of inertia at the expense of working classes and marginalized groups. The government’s incompetence during the pandemic (e.g. the vaccine rollout mess) did dissuade trust in the government but pushed many individuals towards a far-right authoritarian or fascist stance, motivated to defend their individual rights and ‘freedoms’ from lockdowns, vaccine mandates, and so forth, rather than fostering a concern for the welfare of the most vulnerable (frontline workers, minority groups, refugees, Indigenous communities, etc.).

In Indonesia and the Philippines, mass-scale social unrest is a part of very recent history and continues to shape the experience of activist organizing and collective resistance in both countries. It was in 2018, while I travelled through Java’s punk scenes, that I was first introduced to the term gotong royong, which translates as mutual assistance. It was the perfect way to make sense of the community solidarity that underpinned so many leftist punk spaces. Within days of an earthquake hitting a small island, or a community member requiring urgent medical care, groups of punks, artists and anarchists would jump into action – you would find a poster advertising a fully lined-up solidarity gig, featuring stick and poke tattoo artists and screen-printers offering their services for pay-what-you-can donations. Coming from a small punk scene in Canada, I had never before witnessed this level of communal care and radical altruism. One could imagine how vital this rooted spirit of gotong royong would be as the pandemic rolled in, amplifying the existing health and financial crises that the working classes face. Of course, as I shifted my attention to grassroots activist spaces, gotong royong came up again: “You see this because the activists, they really jump out of their way to help the others. And I don’t even know how they do it, like I don’t even know where they get their money from” (Climate activist, Jakarta). The idea, then, of engaging in mutual aid surely incorporates a degree of spontaneity, but its consistency may be driven by something deeper, beyond the condition of necessity. Furthermore, the practice of communal work is anchored in cultural values, which themselves are enmeshed with pre-colonial religious and spiritual practice (i.e. Kejawen or Javanism).

On a similar wavelength, activists in the Philippines spoke about the concept of bayanihan, a Tagalog term that refers to the spirit of unity and cooperation. It stems from the practice of relocation in rural areas, as explained below:

It started from that part in history where someone would need to move their bahay kubo, our cultural house made of cogon and coconut and bamboo, and they would really carry the house and help that neighbour move it.

(Environment and animal rights activist, Manila)

A bahay kubo house would typically require over a dozen people, working in unison, to be physically relocated. It reflects, in the simplest of ways, that things get done more effectively when people move together. But it also evokes the care and benevolence of a people who have long lived in communal settings and fostered interdependence as part of their daily practice. The term bayanihan, however, can be interpreted as nationalist. A more suitable, decolonized concept would be kapwa-tulungan which means mutual cooperation and having concern for one another[iv]. Kapwa prioritizes collective humanity over other values like money, power, the state and even religion. This extends to a deep-rooted care for the natural world. Suppressed under colonial rule, the ancestral spirit of kapwa is rekindled and embodied today through forms of mutual aid and community support. This idea aligns with Kropotkin’s theory of mutual cooperation as inherent across the human species.

Throughout 2021, the Community Pantry movement in the Philippines made waves globally, with families and groups across the country engaging in this simple yet powerful display of mutual support. Despite the government’s attempt to dissuade the movement with red-tagging[v] threats – reflecting the government’s jealousy of autonomous mutual aid initiatives[vi] – the fundamental message of ‘take what you need, give you can’ resonated loudly and clearly. Community pantries were recreated at a grassroots level for months, though the government and other corporate-backed organizations began to co-opt the movement for themselves as they realized just how effective and popular it had become.

Activist and anarchist collectives embody the spirit of kapwa in their practice through a plethora of solidarity initiatives, independently of the pandemic. It should be noted, additionally, that the archipelago’s geographical location and vulnerability to natural disasters amplifies the need for fast-acting community assistance. For example, EtnikoBandido, an anarchist infoshop located in Manila, engages in grassroots autonomous response to communities devastated by typhoons. They not only provide free food and solar power to people on the ground, but also use the opportunity to discuss the impacts of the climate crisis and the value of building resilient, self-managed communities. As argued previously, this ethos of mutual support and cooperation is embedded in pre-colonial, traditional practice, but remains extremely relevant in a country that is riddled with instability due to an authoritarian leader and a highly susceptible natural environment. That being said, anarchist groups like EtnikoBandido consistently engage in mutual aid – independently of crisis responses – as their organizing space in Manila doubles as the site of a daily free shop, community pantry, and public resource center.

Mutual aid initiatives have flourished and multiplied across all three countries since the onset of the pandemic. Such initiatives are likely to ebb and flow as the COVID-19 crisis loosens its grip, hopefully having produced new networks and pathways of cooperation among neighbours and comrades that will maintain momentum as the state attempts to re-establish control. I anticipate, however, that it will take more for us in places like Australia to weaponize our privilege and meaningfully participate in a collective struggle when the majority of the people around us are touting a rhetoric of “she’ll be right” rather than “nothing is alright”. How do we sustain the important work of building grassroots community resilience, in the spirit of gotong royong and kapwa, against the grain of indoctrinated individualism and the state’s repression of grassroots organizing?

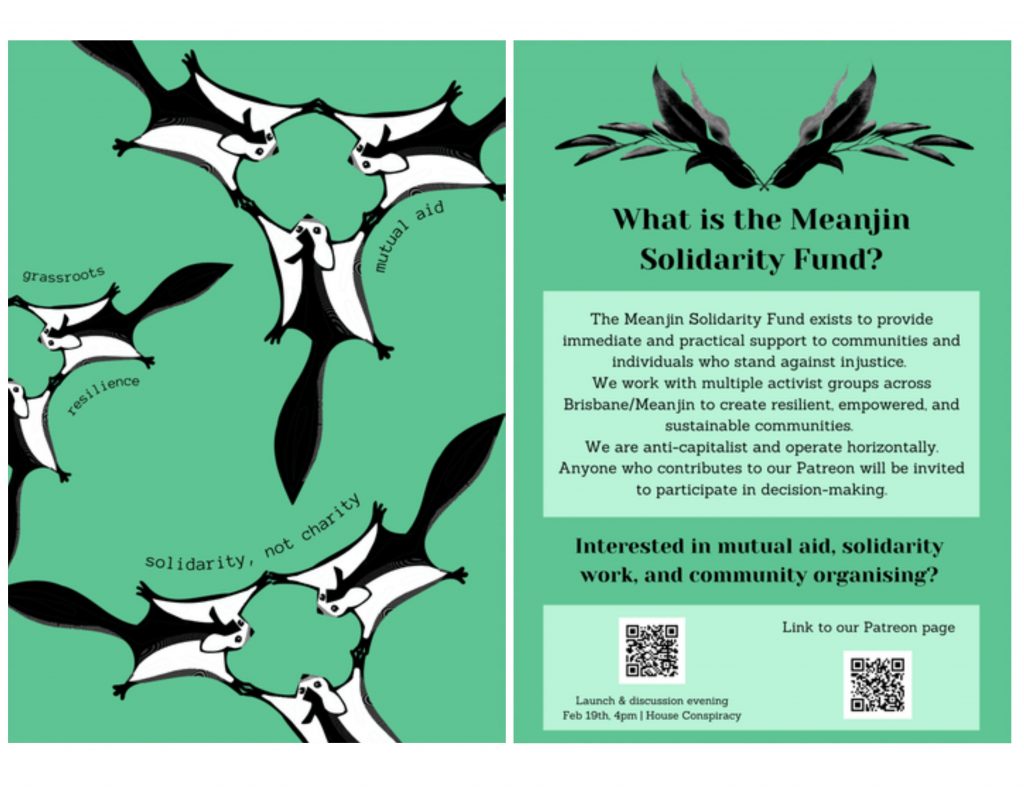

Luckily there are small bastions of collective action that have survived in leftist activist communities and punk-influenced spaces across Australia who practice the ethos of Doing-It-Together. Here are a few examples from Brisbane/Meanjin[vii] . Anarchist Communists Meanjin engage in solidarity work with comrades both locally and abroad, notably through benefit gigs and solidarity fundraising events in their collective space. The Queensland Anti-Poverty Network builds grassroots resistance to fight poverty through targeted campaigns and facilitates mutual aid initiatives from car care clinics to conversational English classes. Indigenous-led groups like Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance frequently utilize their networks to facilitate urgent mutual aid requests from Indigenous Australian individuals or families hit with hardship, and organize large public rallies for Indigenous justice. The Solidarity and Defence Fund based in Melbourne, modelled on the International Anti-Fascist Defence Fund, has successfully supported activists, indigenous and refugee justice struggles since 2017 through a democratic, horizontal model that prioritizes solidarity over charity. Inspired by this concept, the Meanjin Solidarity Fund was launched in late 2021 to provide a central pool of funds to directly support mutual aid initiatives, grassroots solidarity work, and direct-action campaigns around Brisbane. While some of these projects have emerged – or gained traction – throughout the pandemic, they are not born out of spontaneity or sudden necessity but rather have surfaced as offshoots of existing networks that have fluctuated over the years while navigating the unstable landscape of late capitalism: trying to secure funds without sponsorship or charity status, finding suitable organizing spaces, recovering from interpersonal conflicts among comrades (often rooted in patriarchal behaviors), and surviving burnout from state violence, police brutality and compassion fatigues. The impetus of Doing-It-Together may have spilled over into mainstream spaces over the course of the pandemic, making ‘community’ a buzzword for the state and corporations to weaponize in their own way[viii], but there is more than enough evidence to prove that this ethos thrived in alternative, leftist spaces far before the first wave of COVID-19 hit the country. As pre-pandemic examples of gotong royong in Indonesia and kapwa in the Philippines demonstrate, the practice of Do-It-Together is rooted in something far deeper than a mere crisis response.

We will do it ourselves, because the government won’t do it for us.

But we must do it together, because we are stronger as a collective than we are as individuals.

References

[i] Kropotkin, Peter. 1902. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. The Anarchist Library version. Retrieved from https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/petr-kropotkin-mutual-aid-a-factor-of-evolution

[ii] Morales, Cristopher. 2021. “Article: Mutual Aid in the COVID-19 Crisis – a Short-Lived Exception?”, AnarchistStudies.Blog. April 27. Retrieved from https://anarchiststudies.noblogs.org/article-mutual-aid-in-the-covid-19-crisis-a-short-lived-exception/

[iii] Horne, Donald. 1964. The Lucky Country: Australia in the Sixties. Ringwood, Victoria: Penguin Books.

[iv] Lagdameo-Santillan, Karina. 2018. “Roots of Filipino Humanism (I) ‘Kapwa’”, Pressenza, July 24. Retrieved from https://www.pressenza.com/2018/07/roots-of-filipino-humanism-1kapwa/?fbclid=IwAR2UCZmAFsvc50s3mzFCzGhi2PFGRRIs_OVf8APKw6eFJc31cCtTSNQCjE8

[v] The blacklisting of individuals or organizations critical or not fully supportive of the government. Individuals and organizations are “tagged” as either communist or terrorist (or both), putting their livelihoods at greater financial, social, and physical risk.

[vi] Donaghey, Jim. 2021. “A Jealous State? The character of Covid government in the UK”, Academia Letters, Article 298, p.1-6. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/45247352/A_Jealous_State_The_character_of_Covid_government_in_the_UK

[vii] Meanjin is the Indigenous name for the central part of Brisbane city.

[viii] For more on this, see: Gibson-Graham, J.K. 2006. A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 84-85.