by Neil Middleton

5th May 2020

The day after COVID-19 is still a long way off and the full extent of the disruption and damage is unknown. With a new round of crisis getting underway we can at least draw a line under the previous round that began in 2008 and see what can be learnt from those years. For many, the last decade was a time of disappointments, defeats and setbacks as the capitalist system was wounded but survived its great crisis while the price for that recovery was passed down to the lower levels of society. While acknowledging those failures it’s clear not all efforts were in vain and we can use the experience as a platform for the next round.

Out of the host of movements and uprisings of the last decade I will focus here on two situations that tell a larger story, and that I personally witnessed. Despite significant differences between the two in recent years, Greece and France have been on similar trajectories. In both we saw popular mobilisations delaying a neoliberal agenda before the inability to build a new political force meant the initiative eventually returned to the state. Much differs between them but there was enough similarity for it to feel as if you were living out the same experience twice. No doubt those who have experience in different regions will recognise the underlying pattern.

A Flame in Athens, A Spark in Paris

December 2018 was the tenth anniversary of the moment that signalled the beginning of the crisis in Greece, the police murder of the 15-year-old Alexis Grigoropoulos. As the commemorations were taking place in Greece the police in France were warning of an insurrectionary situation. The December 2008 revolt in Greece and the gilets jaunes in France were different in many ways but both shattered the façade of content and changed the political atmosphere. These events did not come out of nowhere, they were the result of a rising discontent and distrust between (sections of) society and its rulers. Common to both countries, and beyond, were neoliberal reforms that weakened the social state, squeezed purchasing power and opportunities, and produced a parliament in which no major policies changed no matter what party formed the government. All this was overseen by an increasingly powerful and invasive police presence.

A period of rising tensions preceded both moments. 2006 saw one of the largest mobilisations in the education system in Greece against a series of market orientated measures. The occupations and frequent clashes with the police lasted into 2007 and provided the introduction to street politics for a new generation. In France, the gilets jaunes should be seen in the context of the cycle of struggles that opened in 2016 with the movement against the weakening of the labour code. During the spring and early summer of 2016 the weekly demonstrations against the measures of the Hollande administration grew in intensity till every march became a violent running battle between the police and the autonomous crowds gathered at the front of the march. The government passed the labour reforms, the police put in new restrictions around demonstrations, and the unions backed down ending that round but the crowds that had formed did not feel beaten. The majority of gilets jaunes were people who had not mobilised before the imposition of a fuel tax in November 2018, but many of the trade unionists, leftists and anarchists that had since 2016 been anticipating another round immediately joined this new movement. The combination was explosive and even if an insurrection was forestalled on December 8th 2018 (by shutting down central Paris and flooding the city with police and armoured vehicles) a new movement was born.

The gilets jaunes and December 2008 abruptly changed the atmosphere in their respective states. The riots revealed that a small but significant slice of the population was so discontented that they wanted to do more than just protest. The gilets jaunes were more explicit in focusing much of their anger on one political figure, Macron, but both revolts called into question representative politics by maintaining their autonomy from existing parties and through the self-organisation of the movement. In both cases the revolts did not fit into standard political practices thereby calling into question the legitimacy of conventional politics. This caused fear and confusion among the political class and commentators which endured long after the initial moments of revolt.

This confused and somewhat frightened political class turned to the police for reassurance. Police forces were given increased powers and tactically reorganised. Here the responses of the two states were almost an exact copy. Demonstrators were targeted with the implementation of laws prohibiting face coverings. Such protections are a necessary part of attending demonstrations in countries where tear gas is frequently used, thus putting protesters at risk of breaking the law merely by their presence. A new mobile police force was also created and equipped with motorcycles to tackle the decentralised protesters.

The police response has by some measures been more severe in France than in Greece, but it was the latter that faced the greater crisis. In France we see the state increasing the levels of violence against wider sections of its population and a political centre that has collapsed in on itself and been dragged to the right by Macron. That, however, has so far been a slow burning crisis, though we will have to see what happens once the state seeks to regain its balance after the pandemic. Within 18 months of December 2008 the Greek state’s crisis escalated dramatically when it could no longer finance its debts in the wake of the global recession. The state that had just been challenged by a revolt had to impose a harsh austerity programme driving the economy into a depression. Not surprisingly, unrest spread. The anti-austerity movement that had developed contributed to the fall of the first austerity government in autumn 2011 and brought the country to the verge of a second revolt when the austerity programme was renewed in February 2012. For years afterwards the state’s stability was precarious.

We are the Barricade

The post-revolt situation in our two examples was different in scale but overall followed a remarkably similar path. In both social movements managed to successfully frustrate and delay state actions before the state eventually regained the initiative.

The Greek anti-austerity movement was of course a failure. The final memorandum programme was officially completed in August 2018 and has been put on a semi-permanent footing in the form of continued supervision and budget targets. Only in Greece, however, was a memorandum effectively delayed. The process took eight years, three different programmes and four governments composed of parties from across the political spectrum. The anti-austerity movement was able to seriously call into question a programme labelled as a necessity for the state, the European Union and global capitalism.

In part this was due to the self-defeating nature of the programmes. The massive amounts of austerity killed the economy it was supposed to save. But the programmes were also stalled by the resistance they faced. The protests, strikes and direct actions against the memorandum did, for a while, throw up a barricade against its progress. This can be seen in the years 2012-2014. The mobilisations of 2010-2012 forced the hegemonic centre-left and centre-right parties to huddle together in a coalition to force through the programme in the face of public anger. Despite unleashing a wave of repression the right-wing led coalition of those years was a weak government which suffered setbacks when opposed on the streets. The pace of memorandum measures slowed midway through 2013 when the sacked workers of the state TV station ERT occupied their workplace rather than go home. The right-wing law and order agenda, brought in to deal with resistance, also had certain aspects curtailed. Concessions were forced by the hunger strikes of anarchist prisoners Kostas Sakkas and Nikos Romanos in 2013 and 2014. The strong reactions of the anti-fascist mobilisations after the murder of Pavlos Fyssas contributed to the crackdown on the neo-Nazi group Golden Dawn.

In the end the coalition fell, in part because it lost the support of the ruling Troika of the European Commission, European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund as it evidently could not deliver more measures. This was the result of the mobilisations of 2010-2012. They had not stopped the memorandum, but they made the state so nervous and precarious that an aggressive implementation of the programme was not feasible. In short, the mobilisations bought some time.

A scaled down version of the same scenario played out in France. Between his election in 2017 and the summer of 2018, Macron moved swiftly, brushing aside any demonstrations and strikes. That momentum was dramatically halted in November and December 2018. In addition to some immediate concessions handed out by a panicking Macron, the gilets jaunes threw an unexpected spanner into his agenda. It was not until his government had reorganised the police, ignoring months of abuses along the way, that in late 2019 he was ready to proceed with the centrepiece of his programme, the pension reforms. This time was bought at an extremely high price with one death from a police tear gas canister in December 2018 and dozens of serious injuries and hospitalisations, not to mention the wider consequences of a police force allowed off the leash.

Between the Old and the New

Forcing a stalemate and buying time was, of course, not enough but nor was it insignificant. Popular movements made themselves a factor at the highest political level and gave the thousands of anonymous participants a sense of agency and a role in an arena from which they are normally excluded. Limited as that progress was, it was largely thanks to the emergence of new forces.

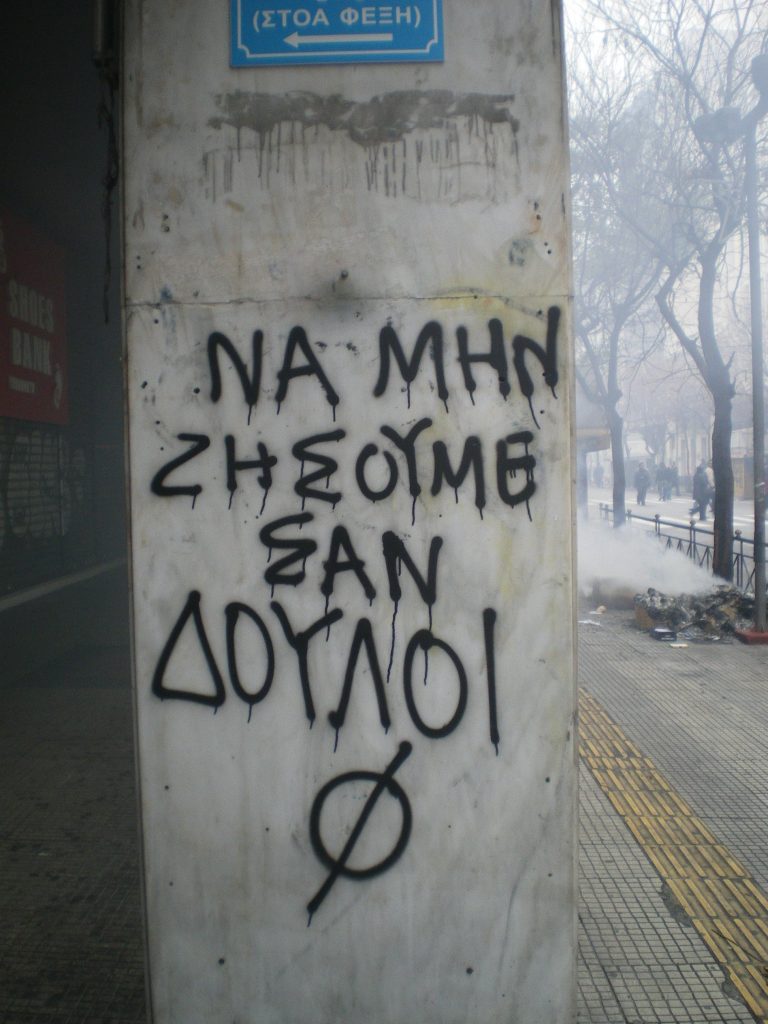

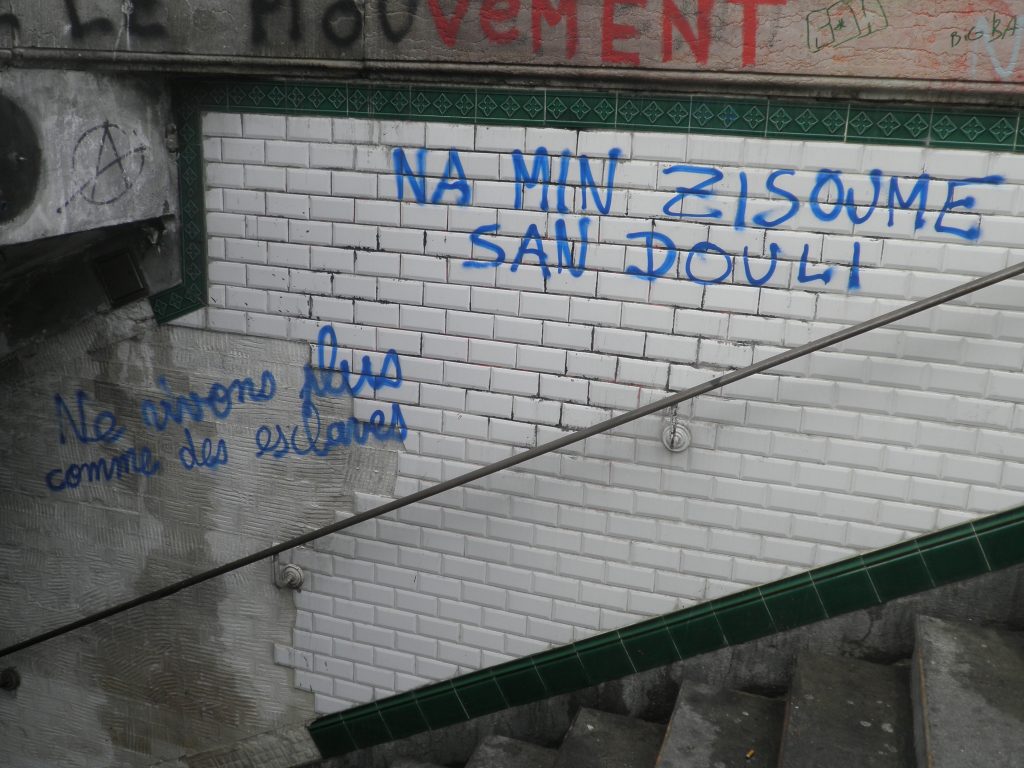

December 2008 is often perceived as an anarchist revolt and, while this not wholly true, it is correct in the sense that an anarchist spirit influenced the movement. It was decentralised and based on direct action and self-organisation, made no demands, and targeted the state and capitalism as a whole. The anti-austerity movement, a popular mobilisation that expanded far beyond any existing political groups, was at its strongest when it had no leaders and was talking about direct democracy.

The anarchist and anti-authoritarian space and the extra-parliamentary left are by no means new to Greece as both tendencies have been significant since at least 1973. For the former, though, this was the first time it played such a prominent role in an historic moment for the country. Both the anarchist/anti-authoritarian space and the anti-austerity movement were important factors in reshaping popular politics in Greece as they contributed to mass movements initially independent from the parliamentary forces that dominated previous decades.

In France, the appearance of a new force often took a physical form. The social movement of 2016 was a shift on the streets from the trade unions to an autonomous and heterogeneous group who went to the front of demonstrations and set the pace and tone, the “cortège de tête”. What started in March as a small group using black bloc tactics grew as more and more people abandoned the trade union blocs behind to join the dynamic groups at the front. By summer there were just as many people breaking away on the “margins” of the demonstration as following the pre-set routine. New movements and ideas have driven other struggles in France in recent years. The gilets jaunes were of course a new crowd in themselves, while the struggle of the ZAD at Notre-Dame-des-Landes, which delivered one of the decade’s popular victories, was a broad alliance of many groups and individuals.

While these new forces clearly have their limits, more traditional forms of struggle were also unable to break the stalemate. Even had the anti-austerity party SYRIZA been better prepared and had an effective strategy in 2015, it is unlikely much would have been different. As the following years demonstrated, they had very limited ambitions in terms of any wider changes to the Greek state. Under their watch the ramparts of Fortress Europe rose higher, crackdowns on solidarity movements and self-organisation continued, relations with the USA were deepened, and little changed in the relationship between the state and the conservative church. In this example, the left party lacked a wider vision of change and only offered to manage the current crises a little better.

It was hoped that the recent battle against Macron’s pension reforms would be the moment when the new spirit of the gilets jaunes and the last few years would converge with the traditional heavyweight trade unions. Despite the heroic efforts of the transport workers who conducted one of the longest strikes in French history during this past December and January, and encouraging signs of the anticipated “giletjaunisation” of the struggle among rank and file workers, by the time all political activity was halted by COVID-19 the battle resembled a more routine tussle between the unions and the government with long gaps between single, predictable days of action. Sadly, it seems the French trade unions were on the verge of losing their effective veto power over unpopular government policy.

These new forces in Greece and France were not a united group in any sense. They were the anarchists, anti-authoritarians, autonomists and extra-parliamentary or radical left. When mobilisations expanded, the majority of people, the gilets jaunes or the citizens in the squares in Greece, didn’t fit into any of these categories. Such a diverse crowd never came together to form a coherent movement, instead its strength lay in action. The riots and protests in 2008-2012 in Greece or France in 2016-2019 frightened governments. The assemblies, occupations and solidarity networks were often ways for the different elements to come into contact and to work on a practical agenda. All of this was done with an explicit emphasis on either direct democracy or autonomy from existing formations. Though there were huge differences within it, particularly with regard to the state and violence, at its best this crowd was able to promote direct action, local community building, and either an outright hostility to (or at least a desire for distance from) existing parties and the central state.

As well as slowing down government agendas this crowd introduced and spread new ideas and forms of struggle. These autonomous and varied groups had a real impact on events. Small and disunited as the different tendencies of these crowds were, their collective actions propelled them from the margins to the central political arena. However, it was not without reason that more traditional political forces, be they parliamentary parties or the historical trade unions, came to dominate the latter stages of these struggles. It was clear that the forces that had brought the government to a stalemate were not generating a force capable of breaking it. So, naturally, many people supported those who promised they could. Unfortunately, once the initiative passed back to more traditional hierarchical parties and trade unions the barricades crumbled and the capitalist response to the crisis got back on track.

Beyond the Barricades

Two of the often-cited problems of radical politics apply to our examples. For all the progress of the new and autonomous forces, these small groups ended up largely isolated and unable to promote a larger vision.

2019 saw these new forces isolated in the face of a state counterattack. The Athenian radical neighbourhood of Exarcheia has been surrounded, invaded and occupied since last summer whilst in Paris the gilets jaunes have been unable to retake the Champs-Élysées, as every group of people that gathers is instantly outnumbered by scores of riot police. Anarchists, anti-authoritarians and radical leftists are small political minorities who, alone, cannot fight the power of a repressive state. Social movements are not doomed to physical or political defeat. To survive they need to grow, so that when the state does strike there is a network of support, and in order to start creating the communities that will replace the old world.

Moving from the margins to challenge the state and capital’s grip on society means building bases and support, be they unions, local communities or solidarity networks. Such work is a process not a single event. There was a tendency in the last round to view the crisis as a series of battles. In Greece that was primarily the battle against the memorandum. In France there has been a series of individual battles against each of Macron’s initiatives. The problem is that a small political minority cannot win every time; in fact, we will almost always lose. You can only win such decisive set-piece battles if you have equal forces. Without such equality of force we have to avoid a simple win-or-lose mindset. We will lose many struggles. Between 2016-2018 in France we lost every battle – the labour code was loosened twice, large parts of the autonomous zone of the ZAD were destroyed and other strikes were defeated – but still momentum was built. We cannot expect to overturn every state decision, but in each of those struggles we will be advancing so long as we are building our own and our communities’ abilities.

Though necessary, a problem with focusing on small-scale actions is the risk of ignoring the magnitude of modern events. Local solidarity networks and similar responses to crises are invaluable in themselves but they are not a challenge to the central state. In the neoliberal era of the hollowing out of the state, these groups are often occupying terrain already abandoned by the state. Our era is one of systemic crisis. Its symptoms are financial, social and environmental breakdown, the increase and normalisation of emergency powers and surveillance, and the degradation of the ideas of asylum and hospitality. The response we envision has to be on a grand scale, even if it is made up of small building blocks.

Creating a vision on that scale was a problem in Greece. The austerity programme’s strongest point was that it was set as the non-negotiable price of staying in the Eurozone. Since its foundation almost two hundred years ago a principle motivation for the state project in Greece has been the desire to be seen as a modern advanced western state, a status confirmed by Eurozone membership. Abandoning the memorandum meant abandoning that goal. The legitimating narrative and the sense of purpose of the state and society was called into question.

The memorandum as a set of policies was defeated in the court of public opinion, as the mass demonstrations and the referendum of July 2015 showed. Less obvious was what would have followed the expulsion of the Troika, or the Troika’s expulsion of Greece. Some thought and activity were put into the immediate consequences of surviving a default and chaotic change of currency, but that’s as far as most horizons stretched. Going beyond the memorandum required the articulation of a whole new narrative of what the Greek state and society’s political project is. Without these larger visions to orientate actions, people were left constantly reacting to state initiatives and never able to move forward. Proclaiming revolt and revolution sounds rather hollow if all people understand is that their lives will immediately become more difficult in the service of a vague undefined goal.

Part of creating a larger vision has to be understanding how that fits into the local context – on one level how it fits into that society’s history, and how that will then connect to the wider world. Paradoxical as it sounds, one of the steps necessary to move forward will be to look back. We all, consciously or not, place ourselves in history to understand where we are, what is happening, and what we aim to do. These narratives have an impact, for example helping people swallow the memorandum to defend their place in “Europe”, or, in the opposite direction, underpinning a desire for Brexit in Britain as a return to the island nation. One aspect, then, of creating and propagating a vision of the future is an alternative historical narrative that can help larger groups of people understand what we are proposing and help ourselves orientate our actions towards a strategy.

It would be dangerous to think that the next round of crisis will play out like the last but there are lessons that can help us prepare. In the last round we saw the failure of a variety of approaches ranging on the traditional spectrum from “electoral” to “movement”. By looking at two of the most prominent theatres of crisis in recent years we can see that despite their limitations the politics of direct democracy, direct action and self-organisation was making progress. It was those principals that helped build the barricades that gave people a chance.