by Wangui Kimari

3rd December 2018

When we remember Palestine in Mathare, Nairobi, the second largest poor urban settlement in the city, what is always evident to the residents who participate in these solidarity events is that, while Palestinians live in a particular and protracted situation of settler colonialism, many of the conditions that they each face are similar.

In this poor urban settlement, almost as old as Nairobi itself, mothers lose children to disease, hunger, and police guns. Like their kin in Palestine, they face derogatory narratives about their right to exist, and young people are put in jail at the whim of a criminal government. It is police officers who function as the face of an illegal and intentionally negligent state, and likely Palestinians may feel the same about the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).

Here in Mathare Stephanie Moraa, a 9 year old shot by the police during the post election protests in August 2017, reminds us of 11 year old Yaser Abu al-Naja, who was the sixteenth child from the Gaza Strip killed by Israeli forces since March 30th this year, the launch of the Great March of Return.

In their actions to demand rights and returns, it is not just the destroyed olive groves or villages, evictions, demolitions, unemployment, hunger, stunted growth, intentional starvation and dehydration, hyper-surveillance, high-density life, and the raids, in their various violent iterations, that are targeted by the people of Palestine and Mathare. In these determined struggles for dignity they also establish, by demands and not petition, that to march is their right, returning home is their right and that their home(s) must be returned.

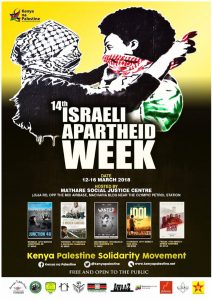

Together with Kenya na Palestine (also known as the Kenya Palestine Solidarity Movement – KPSM) we at Mathare Social Justice Centre (MSJC) work to connect the trades of terror that keep our collectives lives, in Kenya and Palestine, under siege. Currently, as Israel seems bent on establishing more intimate diplomacy with Kenya and targets the strengthening of ostensive “partnerships” on the African continent, even as it deports thousands of Africans from Israel, what this has ensured is that the teargas, guns and tactics used on protesters in Gaza and used on citizens in the streets of Nairobi is of the same type.

In the 1940s, Mathare residents, and Kenyans of all communities, intensified their fight against colonialism. In their homes and workplaces they established creative networks of self-determination to support the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA), more popularly known as the Mau Mau. As a consequence, during this period and into the “emergency years” (1952-1960) preceding independence, this area was recognized as the heartbeat of urban anti-colonial activity in Kenya. So much so that in 1954, in an action known as Operation Anvil, the British colonial government bulldozed houses in this area, and detained the majority of Mathare dwellers – women were moved to “reserve” villages and men were sent to detention camps. They could have no rights, and were not meant to return.

Though the Nakba in 1948 marks a key moment in the expulsion of thousands of Palestinians from their homes, this displacement had already been ongoing for a number of years, connected, as it was in Kenya, to the British. Its many violent effects – of dispossession and statelessness and much more – have for decades continued to reproduce and negatively shape the lives of Palestinians. In Kenya, the years of pronounced displacement and criminalization of indigenous populations (intensified during the 1940s and 1950s) also continue to have many destructive effects on the lives of, principally, poor citizens.

Against their own backgrounds of dispossession, but, above all, their deep humanity, Mathare residents diagnose, viscerally, the many layers of violence enacted against Palestine people every day.

Their recognitions of injustice at home and beyond animate the social justice centres that charge against extrajudicial killings and police violence at great risk to themselves, the youth ecological justice work fervently challenging the historical environmental apartheid in the city and country, the determined work of the Kenya Palestine Solidarity Movement, the visions of the writer/activists who come together at The Elephant, and even the everyday actions of poor mothers to demand water for their communities. These are everyday people movements, like those in Palestine, for life, rights and returns; actions of “impossible possibility” (Sexton, 2012).

Even though they have never been to Gaza, and in their bodies will not experience the particular nuances of state and internationally sanctioned apartheid imposed on Palestinian people, they know and are inspired by their marches for return; their determined steps for rights, for whom many deaths have been proclaimed.

In the struggles of the Palestinian peoples, Mathare residents see their own resolve to keep walking forward, never turning back, never (re)turning to a normalization of violence.

And in this way, they make it clear, that they will never accept a situation of no rights, and no returns.

References

Sexton, J. 2012. “Ante-Anti-Blackness: Afterthoughts.” Lateral 1 (Spring)