by Thomas Swann

15th May 2020

[A German language translation of this article is published in espero journal (Jan 2021)]

If you’d told an anarchist that in May 2020 there would be thousands of groups across the UK aligning themselves with the idea of mutual aid you would have been laughed at. Yet here we are. The coronavirus crisis has seen anarchists proved right about the tendency in social groups towards mutual aid, with networks forming in communities to support those worst affected by social isolation and lockdown. Although the term mutual aid has entered public discourse, this does not mean that suddenly hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people have overnight become anarchists. While these mutual aid groups have latched onto the idea of mutual aid, the conditions that anarchists have identified as being most conducive to effective mutual aid – conditions of self-organisation – are perhaps not immediately apparent. I want to suggest here that the present crisis (as Jim Donaghey argued on this blog) presents an opening for anarchism, and that reinforcing self-organisation in mutual aid networks may be one way in which that opening may be pursued. If mutual aid groups might form a part of how we re-imagine the post-crisis world, then how can we ensure that they not only create new economic structures of resource distribution but also new governance structures of participatory and democratic self-organisation? Towards answering this question, in this article I want to turn to cybernetics and its relationship with anarchism and discuss how we can understand mutual aid networks as viable self-organised systems and how this might underline the importance of democratic self-organisation in how they are governed.

Cybernetics might sound like a fantastical concept, and the word often conjures science-fiction images of cyborgs and high technology. In the latest Star Trek series, one of the characters (an expert on artificial intelligence and synthetic life) was described as a cyberneticist and made mention of reading the Journal of Cybernetics. While the prefix ‘cyber’ was for a time the go-to shorthand for all things technologically futuristic, from cybermen to cyberpunk, the word itself has ancient roots. Plato uses the Ancient Greek term kybernetes (κυβερνήτης) to compare the art of steering a ship with that of government. Ampère, around 2,000 years later uses the French cybernetique this time to speak of a science, rather than an art, of government. At its most basic, cybernetics refers not necessarily to anything technological but to processes (arts, sciences, mixtures of both) of self-organisation in systems. While this can indeed mean technological systems it also applies to social systems like those that Plato and Ampère were interested in (although neither used their versions of the term to refer to governance that would mirror what we today understand as political self-organisation). Norbert Wiener, considered the founding father of cybernetics as an academic discipline, defined cybernetics as the science of control and communication and although it was first developed after the Second World War in relation to biological, electrical and mechanical systems it would soon be applied to social systems and to governance of organisations. What cybernetics aimed to identify were universal principles of self-organisation, and it is here that connections with anarchism and mutual aid can be made.

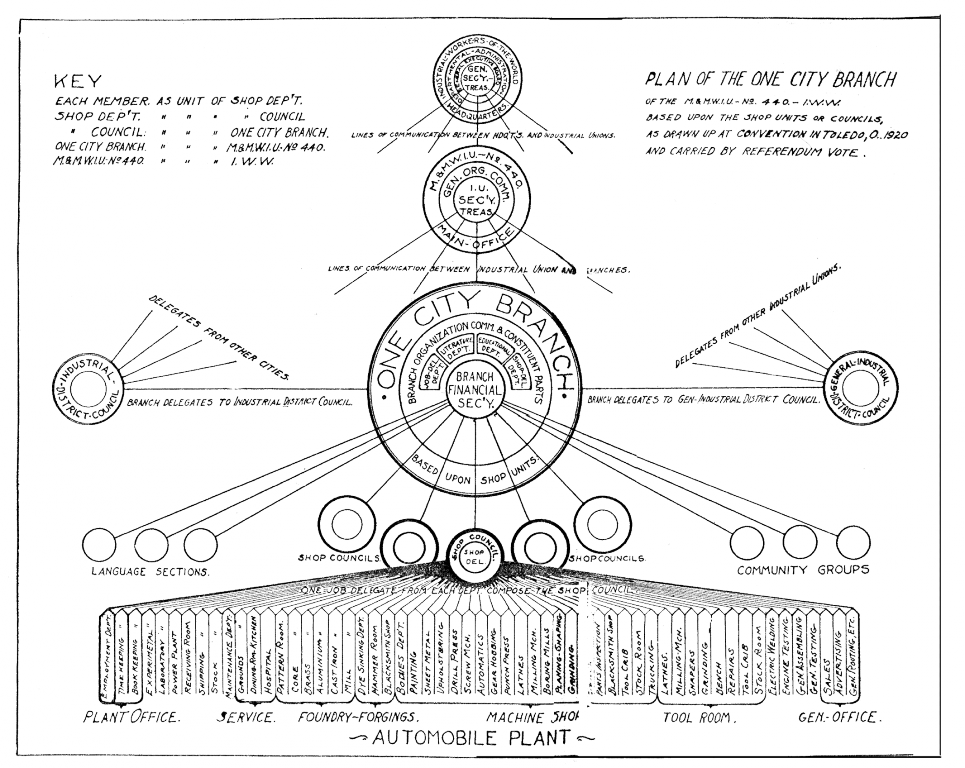

In his essay ‘Anarchism as a Theory of Organization’, published in 1966, Colin Ward wrote that ‘with its emphasis on self-organizing systems, and speculation about the ultimate social effects of automation, [cybernetics] leads in a similar revolutionary direction’ as anarchism. Ward was taking inspiration here from two articles published in 1963, in the journal Anarchy that he edited. The first of these was written by William Grey Walter, a leading cybernetician and roboticist and father of Nicholas Walter who, with Ward, was one of the key figures in anarchism in the UK at the time. Grey Walter’s article introduced readers to cybernetics and how principles of self-organisation in systems can be applied to biological and social systems. He noted that ‘if we must identify biological and political systems our own brains would seem to illustrate the capacity and limitations of an anarcho-syndicalist community’. These connections between how biological and other systems are organised in decentralised ways, without recourse to central control mechanisms, and anarchist approaches to organisation were outlined in more detail by John D. McEwan.

McEwan, who as far as I can determine contributed only this one piece in Anarchy (preceded by a short letter responding to Walter’s article) and was otherwise not involved in debates in either cybernetics or anarchism, wrote the following:

The basic premise of the governmentalist – namely, that any society must incorporate some mechanisms for overall control – is certainly true, if we use ‘control’ in the sense of ‘maintain a large number of critical variables within limits of tolerance’. […] The error of the governmentalist is to think that ‘incorporate some mechanism for control’ is always equivalent to ‘include a fixed isolatable control unit to which the rest, i.e. the majority, of the system is subservient’. This may be an adequate interpretation in the case of a model railway system, but not for a human society. The alternative model is complex, and changing in its search for stability in the face of unpredictable disturbances.

For McEwan, anarchist self-organisation shows how social systems can respond and adapt to change and realise their goals through dispersed process that rely on the autonomy of the parts of the system, working in concert where needed, rather than any centralised, top-down dictatorial behaviour.

Control is defined in cybernetics not, therefore, as top-down, centralised command but as the process through which a system maintains an internal balance or equilibrium, achieved through autonomous and decentralised coordination. This mirrors how the concept of balance was seen by classical anarchists such as Proudhon and Kropotkin. According to Kropotkin, in ‘Anarchism: Its Philosophy and Ideal’, the harmony of an anarchist society functions along similar lines as the harmony of matter in space. Moving away from theories that put either the Earth or the Sun at the centre of the universe, around which everything else in space orbits, Kropotkin notes that the science of his day viewed the movement of heavenly bodies as a complex network of objects interacting with one another, finding a balance where each part moves on its own path in harmony with every other part. In a similar way, anarchist society, he wrote, ‘looks for harmony in an ever-changing and fugitive equilibrium between a multitude of varied forces and influences of every kind, following their own course’. Thus for anarchism as for cybernetics, self-organisation can be understood as a system finding equilibrium in the absence of any dominating organisational force. Cybernetics helps identify how these processes of self-organisation operate, and insights from biology and mechanical engineering are applicable in social organisation, because even though these are very different systems, they have in common their basic functioning as systems that try to remain stable in the face of complex change without central control. More than perhaps that of any other cybernetician, the work of Stafford Beer explores the cybernetic understanding of self-organisation in social organisation.

Beer worked as a management consultant, applying cybernetics to the effective organisation of large corporations, but in the early 1970s became intimately involved in politics when he was invited to advise Salvador Allende’s newly elected government in Chile. Allende wanted to reform the Chilean economy to better provide for the people and involve worker participation in the running of industry. To achieve this, Beer was brought on board to help develop a communication network that would facilitate real-time self-management of the economy, by ensuring that information travelled quickly to where it was needed, allowing workers in factories to make decisions autonomously. As Eden Medina shows in her book Cybernetic Revolutionaries, Project Cybersyn, as the network was called, was never fully realised due both to a lack of technology and Allende’s government being overthrown in the brutal CIA-backed coup, leading to Allende’s death on 11th of September 1973. While Medina and others have argued that the technology behind Project Cybersyn could be applied by authoritarian government, for Beer it also held the promise of effective democratic governance. By both allowing for the parts of an organisation to have a level of autonomy in decision making and ensuring democratic control over any rules and common agreements between these parts, the technical account of self-organisation in cybernetics takes on a character more recognisable to anarchists and others interested in political self-organisation.

Beer was no anarchist, and in a lecture he gave in 1975, titled ‘Laws of Anarchy’, he contrasted the bomb-making student – presumably intended to refer to those explicitly identifying as anarchists – and a state governed by representative democracy, which he characterised as being truly without rulers. This is of course a picture of democracy anarchists would reject, both on account of the impossibility of a non-authoritarian state and the ills of representative democracy. However, if the core of Beer’s argument is that cybernetics shows how effective democratic self-organisation can function, then there is a point of agreement, a point that Ward and McEwan were keenly aware of. The difference stems from how the democratic aspect of political self-organisation is understood. Notwithstanding some anarchist rejections of the concept of democracy, if we take this to involve participatory decision-making of one form or another, with governing practices, rules and institutions agreed collectively, then cybernetics has much to offer anarchism insofar as it helps articulate how self-organisation functions effectively. While mutual aid networks may not be anarchist, if what cybernetics teaches us about the effectiveness of self-organisation is true, and given mutual aid’s intimate connection to anarchist articulations of self-organisation, then perhaps it makes sense to think about how the groups that have formed in the face of the coronavirus crisis can be seen as self-organised systems.

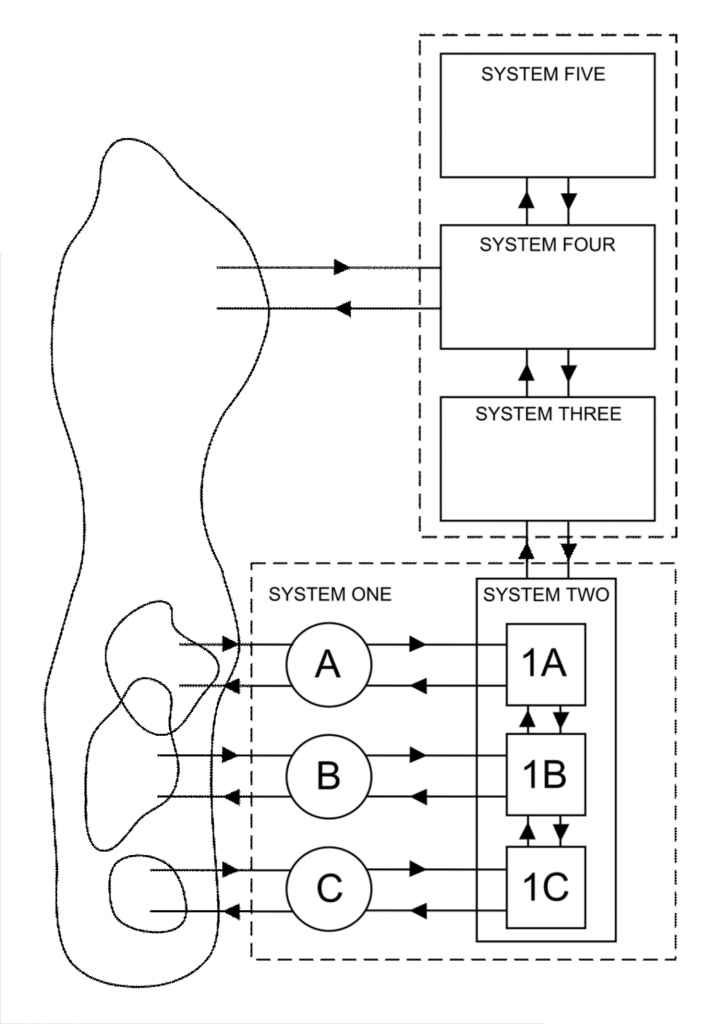

Beer’s cybernetics is encapsulated in his vision of an effective, self-organised system, in what he called the Viable System Model (VSM). Beer shared some of anarchism’s concern for blueprints, and the VSM, despite its name, was intended not as a model for organisations to copy but as a tool to be used by those in organisations to arrive at an understanding of how they could function as self-organised systems. The VSM, in simple terms, helps identify the different functions that need to be produced in any effective organisation, and is divided across five sub-systems, each with its own specified role. System One represents the basic operations of the organisation, operating with some degree of autonomy in their own niches. System Two represents the coordination function between System One units, manifest in formal and informal lines of communication that help avoid clashes and conflicts between them. System Three is where the operations of System One units start to become part of an overarching organisational framework, with an overview of the organisation as a whole and an auditing of System One activities in line with the aims of the organisation. System Four is the strategic function of the organisation, with a view of the environment outside and of how the organisation orients itself towards its goals in response to changes in this environment and those happening in the organisation itself. System Five represents the ethos or identity of the organisation and contains the rules and goals that the organisation’s various activities come together to work towards.

For Beer, it is also important to recognise that any viable system will itself be a System One unit of a larger viable system with the functions described above. Likewise, any System One unit will be a viable system comprised of the five sub-systems. What Beer called ‘recursion’ shows how any organisation will be (1) a viable system, (2) itself part of a larger viable system, and (3) comprised of sequentially smaller viable systems nested within it, right down to the individual (who for Beer will also function biologically and neurologically as a viable system).

Beer explaining the Viable System Model and its application in Chile, in a video produced in 1974:

This might seem like a typical hierarchical organisational chart. People at the bottom of the chain of command occupy System One, while executives or leaders sit at System Five, with various levels of management between them. To look at the VSM in this way is a mistake, however. There is a hierarchy at play in the VSM, but it is one of logical orders of decision making and action rather than the kind of structural hierarchy that anarchists oppose. McEwan, in his article in Anarchy, turned to another influential cybernetician, Gordon Pask, who drew a distinction between ‘anatomical hierarchy’ and ‘functional hierarchy’. Anatomical hierarchy is what we normally think of when we consider a hierarchical organisational structure. Functional hierarchy, on the other hand, refers to something like an ordering of language, with a metalanguage above that is used to talk about the language below. Decisions and actions at Systems Three, Four and Five are logically hierarchical to Systems One and Two activities, but all this means is that decisions at the higher systems come prior to decisions at the lower systems, and insofar as being part of the whole organisation involves some restriction on freedom of choice, determining the scope of autonomy at lower levels.

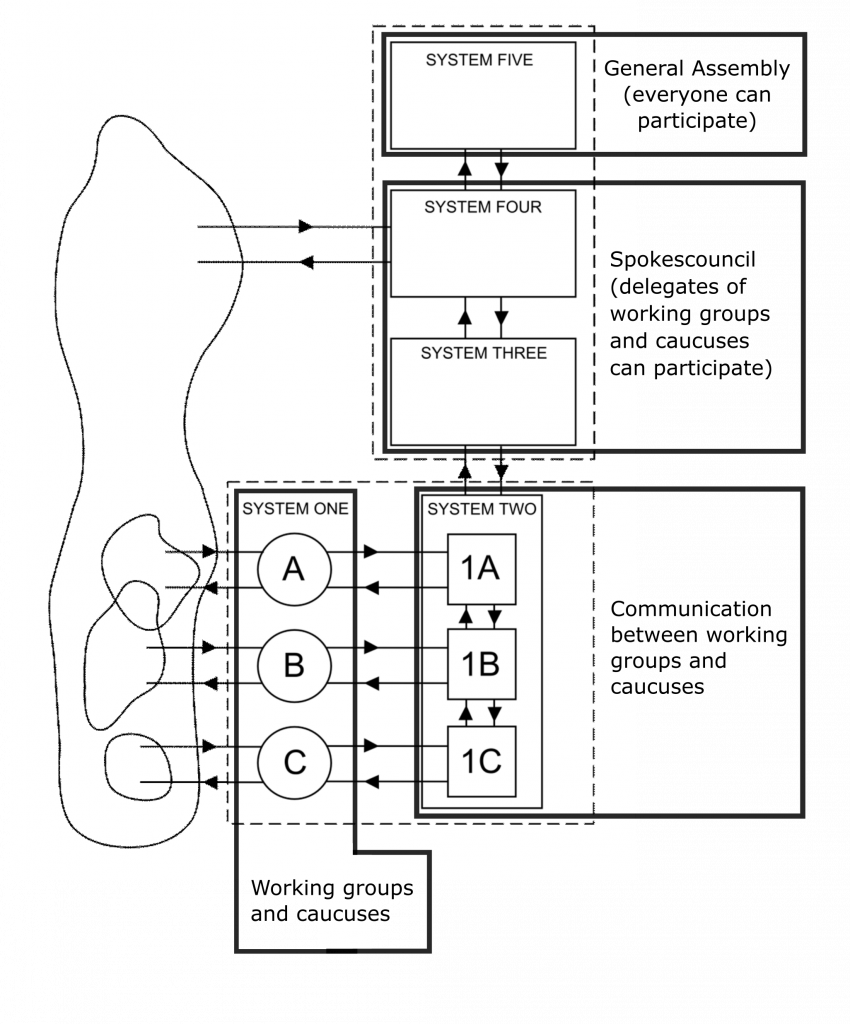

The key to a functional hierarchy that is not replicated in an anatomical or structural hierarchy is that the same people can take part in different functions at different times. Those involved in System One operations can step out of that functional role and take part in System Two coordination discussions and so on. At different times the same people will play different roles in the organisation, being party to decision making about the scope of their autonomy within the organisation as a whole, and any decisions about overarching identity or goals will be made by everyone concerned. This operates much in the same way the standard anarchist model of federation does. Different parts of a federation have complete autonomy in matters that concern only them, but that autonomy is restricted in matters of concern to other parts of the federation. Limitations on autonomy will be decided in forums a step higher in the federation than its individual parts, in ways that all those involved consider fair and democratic. The principle of recursion also reflects the way a federation at a particular level (for example, a specific region) will be a part of a larger federation (at the global level); and every part of the initial federation will themselves be organised with autonomous parts and functionally higher levels of decision making. Occupy Wall Street was organised in a similar manner, with working groups playing System One roles, the Spokescouncil for System Three and Four strategic and logistical decision making and the General Assembly for defining the goals and identity of the camp as a whole. While Beer saw representative democracy as fulfilling this, of putting the people active in System One operations in control of functions from System Five down, for anarchists who reject this form of democratic governance, more participatory and direct approaches to these higher level functions are required.

Mutual aid networks have within them the seeds of this kind of effective, radically democratic self-organisation. While groups will have large differences between them, in many ways they already embody the functions of Beer’s VSM. Split into sub-groupings within a city or similar area, local groups working in their communities make up the System One operations of the organisation. Between them, through communication channels such as WhatsApp groups, System Two coordination will be realised to share both information and resources to ensure that different local groups are effective in providing the support people need. For matters that concern groups across the city or area, such as safeguarding procedures, pooling resources, sharing experience and skills and planning for anticipated change, System Three and Four functions might be manifest in more formalised communication platforms such as Slack or Loomio and through forums held on large Zoom calls between people active in each local group. While the identity and ethos of mutual aid groups is to an extent pre-defined, System Five functions are vital to ensuring that the network maintains its commitment to the normative principles of mutual aid and such discussions might be well-placed to deal with issues such as relationships between networks and local government or voluntary sector organisations. System Five discussions ultimately set the scope for what is and is not included within the remit of the network and although these may only need to happen when disagreement about this remit becomes an issue, it is vital that they are not neglected in favour of more directly-operational activities.

One of the most important things to recognise in this discussion of viable systems and mutual aid networks is that if the networks that exist are operating effectively – in that they are both a source of material and other support to people in need and an organisation that is able to coordinate and share information and resources to enhance that capacity for support – then the functions of Beer’s VSM will be present whether those involved are aware of it or not. If effective self-organisation is happening, then the different functional roles will be realised, regardless of whether anyone uses the terminology of the VSM. This is in part why Beer’s insights about self-organisation chime so well with anarchism, because what he and many in the anarchist tradition have grappled with are the same realities of viable self-organisation. The VSM and the anarchist federation are so similar not because of any shared historical pedigree (to my knowledge there is none, in spite of some overlaps at key points) but because they both in their own ways show how people can organise without rulers. By highlighting the functions of effective self-organisation, in the vein of Beer’s VSM and cybernetics, anarchists and others involved in mutual aid networks can think seriously about organisational structure and about why certain problems emerge in the ways that they do.

The challenge as mutual aid networks develop and potentially extend beyond the present crisis is to ensure that the functional hierarchy of roles does not become ossified in a structural hierarchy but that it remains open to democratic participation. This is how mutual aid networks can be at their most effective, by refusing to unnecessarily exclude some from decision making processes, and it is how they might form part of the process of imagining an alternative future beyond the coronavirus crisis.

Thomas Swann is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in Politics and International Studies at Loughborough University. His book Anarchist Cybernetics will be published in 2020.