by Joaquín Rodríguez Álvarez

26th November 2020

Context

Our era is being shaped by a set of technological advances that have the embedded potential to transform our relation with our context, due to their holistic approach to the different dimensions of human experience (Ellul, Wilkinson and Merton, 1964; Rodríguez-Álvarez, 2019). This is an era that could be defined by the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and its impacts over the human condition (Arendt, 2014), where its governance and orientation will be key in our battle for survival in the ongoing ecological crisis, which puts us at the edge of the abyss of extinction (Bookchin, 1999). But, technology has two faces, and Artificial Intelligence, while being a key tool for our survival, can also represent a crystallization of the current dynamics of oppression, condemning us to a future of servitude in an algorithmic society.

But before describing the current situation in relation to AI, it is necessary to underline a set of premises to comprehend, on one hand, the nature of the crisis, and, on the other hand, the current state of the technology, to be able to identify those meta-narratives that are intended to deceive us.

The ecological crisis should be understood as an externalization of our productive system and the ideologies that fuel it. Therefore, it can only be addressed through the overcoming of the capitalistic system, understood as being also ideological and cultural (Žižek, 1997; Biehl and Standenmaier, 2019). As Bookchin pointed out:

“To speak of ‘limits to growth’ under a capitalistic market economy is as meaningless as to speak of limits of warfare under a warrior society … Attempts to ‘green’ capitalism, to make it ‘ecological’, are doomed by the very nature of the system as a system of endless growth”. (Bookchin, 1989, p. 93-94)

Related to the current state of the technology and its limitations, as well as the meaning of technology itself, we need again to set some basic premises to avoid falling into science-fiction scenarios when thinking about AI and technology. Skynet or the Singularity (Chalmers, 2016), as interesting as they are as theoretical approaches, are at a far remove from the current, and probably future, capabilities of the system – but they still play an important role in our collective imagination.

First of all, Artificial Intelligence should be understood as a simulation of Intelligence (Baudrillard, 1994), due to the fact that we are not talking about any kind of synthetic being, just a system able to develop complex tasks (as programmed to) with different levels of autonomy (both in the physical and the digital dimensions), while affecting all layers of our experience (Russell, Norvig and Davis, 2010). Any attempt to “personalize” the technology should be understood as a hypostatization, a fallacy oriented to indoctrinate us to accept its social penetration whatever its cost, as we will observe.

Secondly, technology as a whole should be understood, not just as the totality of our material culture (Ellul, Wilkinson and Merton, 1964), but also as an amplifier of human will, as pointed out by Kentaro Toyama (ITU and XPRIZE, 2017). This fact should re-define our approach, interpreting it as value-laden, and not neutral (as it used to be represented) (Rodríguez, 2016).

Thirdly, technology has the inherent capability to determine the ways we relate with and interact with our context (Bimber, 1994). But in any case, this determination should not be understood as inevitable. As Ellul pointed out, “There will be a temptation to use the word fatalism’, but this fatalism is only fulfilled conditionally:

“if each one of us abdicates his responsibilities with regard to values; if each of us limits himself to leading a trivial existence in a technological civilization, with greater adaptation and increasing success as his sole objectives; if we do not even consider the possibility of making a stand against these determinants.” (Ellul, Wilkinson and Merton, 1964 p.30 [emphasis added])

Finally, it’s important to notice that this article does not pretend to take an approach in terms of “bad” and “good” relating to technology, as some anarcho-primitivist approaches do (Kaczynski, 1995), but aims to structure itself as a call for a communitarian governance of technology, and its alignment with an eco-social approach (Bookchin, 1999), observing technology, not just as a tool, but an extension of the human, inherently able to reshape us.

The techno-ecological approach

Technology, as an extension of the human experience, plays a crucial role in the manufacturing of reality, as a structural part of our system (Ellul, Wilkinson and Merton, 1964; Postman, 2011). The notion of progress undoubtedly has a technological component in this system (Marx, 2000), but, foremost, technology is also closely related to power, insofar as it affects the construction, exercise and even perception of power (Rodríguez, 2016). Technology is a complex phenomenon with the inherent capability to liberate as well to enslave us, having “deterministic” characteristics when inserted in a particular context (Bimber, 1994; Smith and Marx, 1994; Chandler, 1995).

But, as Giorgio Colli pointed out:

“Modern scientists have not yet come up with something that for the ancients was obvious: that specific knowledge must be silenced to the few, that dangerous abstract formulas and formulations, with fatal evolutionary problems, disastrous in their applications, must be valued in advance and to a full extent by whomever has discovered it, and therefore must be jealously hidden, removed from publicity. Greek science did not achieve great technological development because it did not want to. With silence, science scares the State, and it is respected. The state can only live, fight and strengthen itself with the means offered by culture: it is something known perfectly well, the chief of the tribe depends viscerally on the sorcerer”. (Colli, 1978 p. 123)

To understand that technology has been a direct source of power, comprehended as not just a means of production but also as a symbol, reinforces an idea of technology that challenges traditional Marxism, allowing us to see the existence of an intermediate group between the oppressors and the oppressed – a technological class (Veblen, 1919, 2009). The existence and size of this technological class depends on the necessities of the system’s operability, from sorcerers and priests to bureaucrats and all those directly involved in the maintenance of the system (all those whose tools of development and control were formerly the object of mystification). Whether interpreting the bible to an illiterate audience whose access to all culture was restricted, or programming AI in a society where most people don’t understand how it works but will uncritically accept its decisions, these different scenarios follow the same pattern – knowledge as power, with technology as its physical materialization. As Simone de Beauvoir pointed out in her work “Ethics of ambiguity”:

“the oppressor would not be so strong if he did not have accomplices among the oppressed themselves; mystification is one of the forms of oppression”. (de Beauvoir, 1962 p. 32)

And today, there is a lot of mystification in the AI world. Therefore, the technological component can define the societal structure, and its evolutions can shake the foundations of that system.

Technology as a frontier

Technology should be understood as a total phenomenon, able not just to amplify our will but to shape it (McLuhan, 1994), giving form to a complex understanding of the context, always limited by our own capabilities. The problem, as pointed out by Kaczynski in his manifesto “Industrial Society and its Future”, is that even though technology has at its core the inherent capability to help us, the practical orientation of the system has led us to a scenario that “deprives people of dignity and autonomy” (Kaczynski, 1995). This is a modern slavery where the nightmares of Orwell and Huxley combine, giving form to a dystopic reality concealed by the entertainment culture (Postman, 2006) where the notion of “liberal democracy” acts as a mere “myth” oriented to generate a sense of freedom, embracing the force of simulations (Baudrillard, 1983). The critical claim, then, is that technological development under a capitalistic approach leads us only to “slavery” through complete alienation, dislocating not only our relationship with nature, but with reality itself.

Therefore, we should recognize that technology per se is not the problem – the problem is the system within which this technology arises. This is a system where even the metaphors we use in relation to technology are deeply value-laden and problematic. We “conquered” fire, as we “conquered” the Americas or “conquered” Space – new frontiers, new discoveries that we have made. And as problematic as the “conquering” metaphor is, it is always a “we”, because neither science, nor knowledge as a whole, can be privatized by any individual or specific community. It’s always a result of a collective effort, as pointed out by Kropotkin:

“Every machine has had the same history – a long record of sleepless nights and of poverty, of disillusions and of joys, of partial improvements discovered by several generations of nameless workers, who have added to the original invention these little nothings, without which the most fertile idea would remain fruitless. More than that: every new invention is a synthesis, the resultant of innumerable inventions which have preceded it in the vast field of mechanics and industry.

Science and industry, knowledge and application, discovery and practical realization leading to new discoveries, cunning of brain and of hand, toil of mind and muscle – all work together. Each discovery, each advance, each increase in the sum of human riches, owes its being to the physical and mental travail of the past and the present.

By what right then can anyone whatever appropriate the least morsel of this immense whole and say – This is mine, not yours?” (Kropotkin, 1995 p. 16)

But the history of science and technology has been written by a few, and suffered by most. Those whose effort in the creative process has been stolen, and those whose worlds have been “discovered” or “conquered”, are always deprived of the control of the means of production. These means of production produce not only commodities, but symbols, myths, ideology, and ultimately consent. The consent that has been produced has allowed the concentration of the 50% of the planet’s wealth in the hands of the 1% of the population (Credit-Suisse, 2019), not only creating, but also justifying the existence of an extractive elite whose agenda is leading us to ecological and social chaos.

That’s why, to revert the current direction of our techno-scientific system, it is necessary to pay attention to those narratives oriented to an acritical acceptance of technology, the implications of which go beyond mere “privacy invasions” to the crystallization of an algorithmic society able to transform every single meaning. War is peace / freedom is slavery [and] ignorance is strength. This would be a system not only able to manufacture consent, but to exercise a complete control over the subject as an extension of the notion of bio-politics (Foucault and Varela, 1978), and the arrival of which is preceded by a set of myths designed to facilitate its social penetration.

The rise of AI and its mystifications

Artificial Intelligence structures itself today as a new frontier in our collective imaginary, being sometimes more a narrative than an actual technology (Bostrom, 2005). This process of technological mystification, that has repeated itself like a pattern in our long-term relationship with technology, allows us to understand the level of interdependence between the “human” and the “technological” (Ellul, Wilkinson and Merton, 1964; Smith and Marx, 1994; Postman, 2011), as well as the implications that AI can have in relation to the human condition (Arendt, 2014).

From the calendar, to Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO), different sets of narratives have been historically set in place in order to “elevate” our technologies from a “technique” to a “symbol” and a “promise”, generating a complex set of meta-narratives, giving birth to a co-production process (Jasanoff, 2003), where we shape our technologies, and then they shape us (Culkin, 1967; McLuhan, 1994). The mist generated from this mix of the hyperreal and the metaphorical gives birth to a new reality mediated through technology.

The emergence of the calendar, a technology associated with the Neolithic revolution allowing the reproduction of agricultural cycles, ended up harboring a type of magical thought related to the traceability of time and its relationship with astral cycles (Calleman, 2004), which further led to systems of oppression and control through the forecasting of complex astral phenomena (eclipse prediction for example) (Ellul, Wilkinson and Merton, 1964; Bernstein, 1996).

This phenomenon also takes place in “scientific societies”. For example, the properties of “radiation” were completely overstated in the 1920s and 1930s, and on that basis radioactive substances were used in the production of general consumer goods of all kinds, including toothpastes, chocolates, skin creams and so on – a clear example of the impact of scientific narratives over society, with significant effect on public health in this case. But this impacts upon freedoms, especially when the myths have structural manifestations over the system, like the “mutually assured destruction” myth (Wilson, 2008), or the myths that came to life in the form of future “promises” of clean, cheap and safe energy sources materialized through programs such as Atoms for Peace.

This is a dynamic that repeats itself constantly, especially when it comes to technologies that are a potential source of change, such as the field of biogenetics. Under the promises of resistant crops and the end of world hunger, a patrimonialization of GMO technology was concealed, whose interests, once again, did not pivot around the common good, but around those of the capitalist production system. The “terminator gene” stands as a paradigmatic example (Ohlgart, 2002), reproducing by its mere existence the dynamics of oppression that operate around the food industry, leading to serious threats to food sovereignty, and a new concentration of the market in even fewer hands than in the last “green revolution” (Shiva, 2016). This is yet another technology with liberating potential aimed at the crystallization of the social order and the consecration of a productive system, which continues to encourage monoculture, despite full awareness of its erosive effects on the ecosystem.

And today, the cycle seems to be repeating itself in the case of Artificial Intelligence. In the first-level international forums, promises about utopian scenarios are again extended, promises that can “only” be reached through a single path: data transfer, privacy transfer and ultimately, humanity transfer (Griffin, 2017; Sharkey, 2018). Users run the risk that much of the data they willingly provide will be used against them, either by private corporations or by military programs, as is already happening with facial recognition (Statt, 2018).

Therefore, it’s necessary to establish a clear base of analyses to overcome the “natural” bias we have in relation to technology – the key element in understanding the impact of AI resides in the observation of decision-making delegations over non-human entities. AI is a phenomenon that exposes us to a new reality, being the first time in the history of our species that we exist in an ecosystem where critical decisions that affect our lives are taken by non-humans (delegation through technology). This is already the reality in instances such as credit scoring, lethal autonomous weapons (Rodríguez-Álvarez and Martinez-Quirante, 2019), passing through loan concessions, university acceptance, teacher evaluations, facial recognition and so on. The “natural” bias is a set of processes that exacerbates the tendency to embody AI with “divine” qualities, or even humanity; as if the AI could be understood as a moral agent, uninfluenced by those “biases” and ideologies that condition our approach to context (Žižek, 1997). The “natural” bias is also grounded on assumptions of efficiency and reliability, on the common belief that machines can do things better and faster than us, so they are called upon to replace us (Barrat, 2013), or to enhance us (Bostrom, 2005).

But reality is much milder than our dreams and expectations, even while we build an algorithmic society that could be interpreted as a manifestation of Baudrillard’s worst fears. This is a place where Orwell meets Huxley and we comfortably submit our few freedoms to the interests of the “machines owners”, a landscape where privacy deludes itself in the reflections of an entertainment culture that alienates us as if it were “Soma”, while we carry the Orwellian control in our own pockets.

Futures of fear and futures of hope

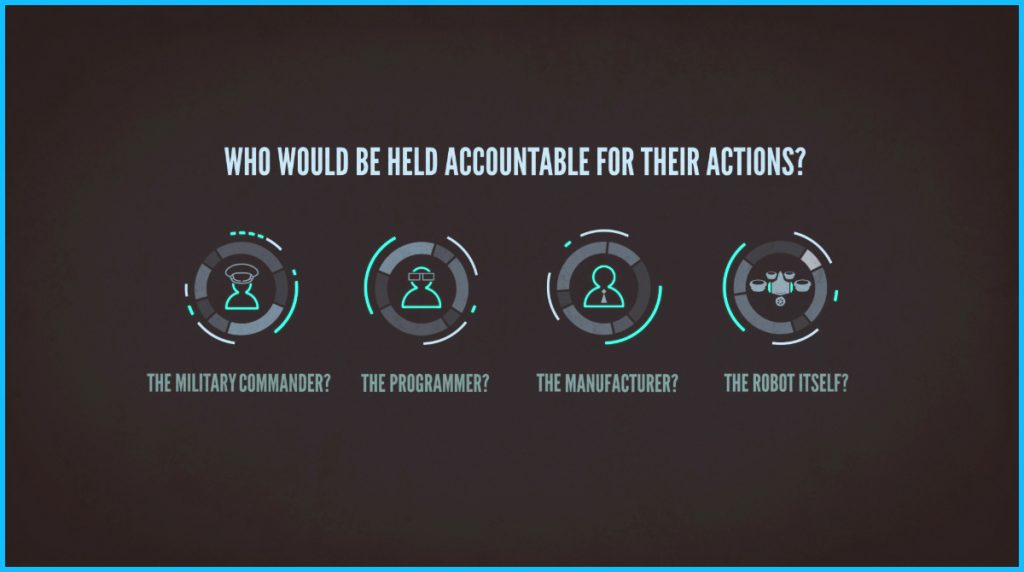

Our technological sets, as pointed to before, have the ability to reproduce and reinforce structures of power (the superstructure) when we resign to their assessments and governance. But we are also developing AI systems specifically design to kill, as is the case with Lethal Autonomous Weapons (Rodríguez-Álvarez and Martinez-Quirante, 2019). This tendency has been described by numerous scholars as the third revolution of warfare (after those defined by gunpowder and nuclear technology) (Asaro, 2012; Sharkey, 2012; Scharre and Norton, 2018; Rodríguez-Álvarez, 2019). The impact of this is difficult to predict, but it represents clear ethical issues (since we are delegating lethal capabilities to machines), as well as legal issues. Their use is incompatible with International Humanitarian law, as it is interpreted at the moment, because this system deludes itself with the notion of responsibility, especially in the existing provisions relating to accountability for civil casualties during conflict (Burri, 2016).

More than any other “unethical” application of AI, the rise of “Killer Robots” (Human Rights Watch, 2014; Roff, 2014) represents the materialization of futures of fear. We are talking about new weaponry systems able to manage critical functions such as targeting, and target elimination, without significant levels of human control; in an autonomous mode. These systems are not science-fiction, the Phalanx System (US Navy) or the Iron Dome (Israel) are among the best-known examples, but there are hundreds, mainly developed by the US, Russia, China, the UK, South Korea, and Israel.

These new weapons systems raise questions around our role in war (this activity could be delegated to machines), questions about the “technological gap” and the new dynamics of oppression that this technology could represent in the international arena, as well as questions on the notion of humanity and the violation of human dignity that these weapons systems represent (Bhuta, 2016). Their existence predicts an exponential rise in extrajudicial executions, as well as an increasing distance between the population and the conflicts fought in their name. Those citizens may lose what little control they have over the military activity of their states, since the fact of not deploying troops will reduce the number of eyes on the conflict (the press traditionally follows the soldier, not the drone).

This dystopian future of social control and oppression, where the machines could do the “dirty jobs”, would reduce human control and knowledge about the pillars that configure our reality. This simulation would allow “first class humans” to live in a kind of “oasis” while the rest of the world burns under the pressure of social control and ecological chaos. But there are alternative futures – futures of emancipation, equality and justice, where society does not adapt to the necessities of technology but vice versa. These could be futures of hope where technology could bolster the recognition of the municipality as the epicenter of political life (Bookchin, 1989), diminishing borders as well as the notion of the state. Imagine smart communities where technology allows new levels of symbiosis with our ecosystems, allowing them to communicate in ways that can be easily translated to us – a new world where stateless institutions can be organized through Block Chain, empowering people in the control of their own data, redefining the meanings of digital property. This could be a society where automation is oriented, not to substitute workers, but to free them, breaking the chain of wage labor in agriculture, transportation or even industrial production, while observing the ecological footprint of our actions. This technology would be at the service of an eco-social agenda that, for the first time, would have the means necessary to establish a new praxis.

To this end, it is necessary to encourage new generations of researchers, technologists, and scientists to rethink technology under a socio-ecological approach, focusing their work into applications that can have a liberating potential, and putting it at society’s disposal.

References

Arendt, H. (2014) La condición humana. 8th edn. Barcelona: Vives.

Asaro, P. (2012) ‘On banning autonomous weapon systems: human rights, automation and the dehumanization of lethal decision-making’, International Review of the Red Cross, 94, pp. 687–709.

Barrat, J. (2013) Our final invention : artificial intelligence and the end of the human era. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Baudrillard, J. (1983) ‘The precession of simulacra’, in Hlynka, D. (ed.) Paradigms Regained. 1st edn. New York: St Laurence University Press, pp. 448–468.

Baudrillard, J. (1994) Simulacra and simulation. 1st edn. Detroit: University of Michigan Press.

Bernstein, P. L. (1996) Against the gods: The remarkable story of risk. 1st edn. New York City: Wiley John and Sons.

Bhuta, N. (2016) Autonomous weapons systems : law, ethics, policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biehl, J. and Standenmaier, P. (2019) Ecofascismo. Barcelona: Virus.

Bimber, B. (1994) ‘Three faces of technological determinism’, in Marx, L. and Smith, M. Does Technolgy drives history? Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, pp. 79–100.

Bookchin, M. (1989) Remaking society. Montreal: Black Rose Books.

Bookchin, M. (1999) La ecología de la libertad. Madrid: Madre Tierra.

Bostrom, N. (2005) ‘A history of transhumanist thought’, Journal of Evolution and Technology, 14(1), pp. 1–25.

Burri, T. (2016) ‘The Politics of Robot Autonomy’, European Journal of Risk Regulation, 7(2), pp. 341–360.

Calleman, C. J. (2004) The Mayan calendar and the transformation of consciousnesss. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Chalmers, D.J. (2016) ‘The singularity: A philosophical Analysis’, in Susan Schneider (ed.) Science Fiction and Philosophy. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Chandler, D. (1995) Technological or media determinism, Wolearn.org. Available at: https://www.wolearn.org/pluginfile.php/45/mod_page/content/23/chandler2002_PDF_full.pdf (accessed November 5, 2014).

Colli, G. (1978) Después de Nietzsche. 1st edn. Barcelona: Anagrama.

Credit-Suisse (2019) The Global wealth report 2019, Credit-suisse. Available at: https://www.credit-suisse.com/about-us/en/reports-research/global-wealth-report.html (accessed December 4, 2020).

Culkin, J. (1967) ‘A Schoolmas’s Guide to Marshall McLuhan’, The Saturday Review. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5a6135761f318d1d719bd5d9/t/5b2536342b6a2886441759d5/1529165365116/JOHN_CULKIN.pdf (accessed March 27, 2019).

de Beauvoir, S. (1962) Ethics of ambiguity. Plessisville: Citadelle Press.

Ellul, J., Wilkinson, J. and Merton, R. (1964) The technological society. New York: Random House.

Foucault, M. (1990) Vigilar y castigar: nacimiento de la prisión. Madrid: Siglo XXI.

Foucault, M. and Varela, J. (1978) Microfísica del poder. 1st edn. Madrid: Endymion Ediciones.

Griffin, A. (2017) ‘Saudi Arabia grants citizenship to a robot for the first time ever’, Independent. October 26. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/news/saudi-arabia-robot-sophia-citizenship-android-riyadh-citizen-passport-future-a8021601.html (accessed April 15, 2019).

Human Rights Watch (2014) The Human Rights Implications of Killer Robots | HRW, HRW. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/05/12/shaking-foundations/human-rights-implications-killer-robots (accessed April 17, 2019).

ITU and XPRIZE (2017) AI for Good Global Summit. Geneva. Available at: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-T/AI/Documents/Report/AI_for_Good_Global_Summit_Report_2017.pdf (accessed March 27, 2018).

Jasanoff, S. (2003) ‘Technologies of humility: citizen participation in governing science’, Minerva, 41(3), pp. 223–244.

Kaczynski, T. (1995) ‘Industrial society and its future’, Washington Post, September 22. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/longterm/unabomber/manifesto.text.htm (accessed November 25, 2020).

Kropotkin, P. (1995) The Conquest of the bread and other Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marx, L. (2000) The machine in the garden : technology and the pastoral ideal in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McLuhan, M. (1994) Understanding media: The extensions of man. 1st edn. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Ohlgart, S. (2002) ‘The Terminator Gene: Intellectual Property Rights vs. the Farmers’ Common Law Right to Save Seed’, Drake Journal of Agricultural Law, 7(11), pp. 473–488.

Postman, N. (2006) Amusing ourselves to death: Public discourse in the age of show business. 20th edn. London: Penguin.

Postman, N. (2011) Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. New York: Vintage Books.

Rodríguez-Álvarez, J. (2019) ‘Rethinking Paradigms in the Technolo-ecological Transition’, Journal of Law, 1(2), pp. 169–184.

Rodríguez-Álvarez, J. and Martinez-Quirante, R. (2019) Towards a new AI race. The challenge of lethal autonomous weapons systems (Laws) for the United Nations. Cizur-Menor: Tomson Reuters Aranzadi.

Rodríguez, J. (2016) La civilización ausente: Tecnología y sociedad en la era de la incertidumbre. 1st edn. Oviedo: Trea.

Roff, H. M. (2014) ‘The Strategic Robot Problem: Lethal Autonomous Weapons in War’, Journal of Military Ethics, 13(3), pp. 211–227.

Russell, S. J., Stuart, J., Norvig, P. and Davis, E. (2010) Artificial intelligence : a modern approach. 3rd Edition. New York: Pearson.

Scharre, P. and Norton, W. W. (2018) Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War Army of None: Autonomous Weapons and the Future of War Arms Control Today. Arms Control. Available at: https://www.armscontrol.org (accessed June 10, 2020).

Sharkey, N. (2012) ‘The evitability of autonomous robot warfare’, International Review of the Red Cross, 94, pp. 787–799.

Sharkey, N. (2018) ‘Get Out Of My Face, Get Out of My Home: The Authoritarian Tipping Point’, Forbes, November 23. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/noelsharkey/2018/11/23/get-out-of-my-face-get-out-of-my-home-the-authoritarian-tipping-point/ (accessed April 15, 2019).

Shiva, V. (2016) The violence of the green revolution: Third world agriculture, ecology, and politics. Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky.

Smith, M. and Marx, L. (1994) Does technology drive history?: The dilemma of technological determinism. 1st edn. Boston: MIT Press

Statt, N. (2020) ‘Amazon bans police from using its facial recognition technology for the next year’, The Verge, June 10. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2020/6/10/21287101/amazon-rekognition-facial-recognition-police-ban-one-year-ai-racial-bias (accessed June 11, 2020)

Veblen, T. (1919) The Place of Science in Modern Civilisation: and other essays. Fairford: Echo Library.

Veblen, T. (2009) The Theory of the Leisure Class, A Penn State Electronic Classics Series Publication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, W. (2008) ‘The myth of nuclear deterrence’, Nonproliferation Review, 15(3), pp. 421–439.

Žižek, S. (1997) ‘The Supposed Subjects of Ideology’, Critical Quarterly, 39(2), pp. 39–59.