by Ruth Kinna and Peterson Silva

13th February 2023

[Also available in Portuguese, here]

Zoe Williams’s potent criticism of body politics and self-loathing, published last month in the Guardian, promotes ‘anarcho-feminism’ as the best answer to the ceaseless, often concealed demands for conformity that blight the lives of girls and young women. We agree, but her tantalising conclusion begs the question: ‘why?’ What’s so special about anarchafeminism as a strategic response to marketised, misogynist messaging?

For starters, anarchafeminism targets Williams’s two twin concerns: capitalism and patriarchy. For anarchists airbrushed from feminism’s history for questioning the value of ‘first-wave’ inclusion campaigns, these institutions were mutually reinforcing. Women’s subjection was partly explained by labour-market discrimination. But employment law reflected prejudices that sprang from the primacy of the marriage market. Groomed to fulfil roles as wives, mistresses or sex workers, women were always auxiliary and dependent. Clerics taught that this was ‘natural’, righteous punishment for original sin. Governments conferred a subordinate legal status that, for example, restricted girls’ access to education and sanctioned domestic violence and marital rape. Women’s role was to conform to disempowering ‘protective’ systems that in fact left them subject to routine abuse.

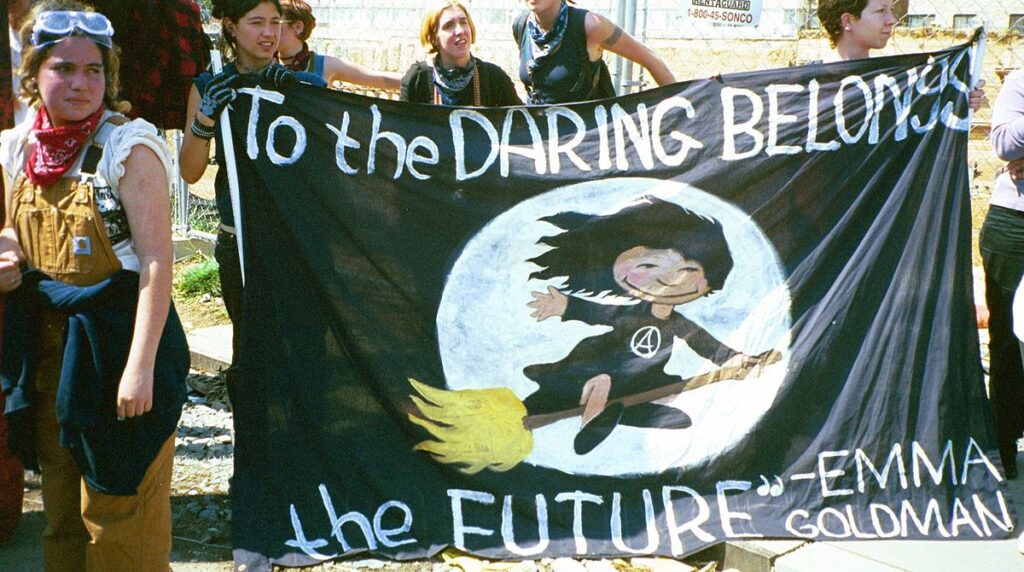

One of Williams’s arguments is that the real message behind body positivity and the exhortation to be healthy is, in fact, ‘be thin’. Probing the social, cultural and economic ramifications of ‘sex slavery’, militants like Emma Goldman and Voltairine de Cleyre took their lead from Mary Wollstonecraft for whom thinness was the visible indicator of sublime incapacity. It mapped to virtues of patience, docility and tenderness. Their cultivation was supposed to hold women’s physical and mental exertion in check; the Romantic ideal of the helpless, pallid, couchbound beauty generated a strongly racialised stereotype to boot.

Anarchist women broadly welcomed the liberalisation of labour markets, but warned that access to employment by itself would not empower independence or social interdependence, the communist anarchist goal. They were right: including women in brutal systems does not feminise the latter, it simply reinforces existing class hierarchies, while leaving cultural prejudices intact. Capitalism remains exploitative, turning a profit by turning women against one another and each one against herself. As labourers, they compete for jobs, depressing wages. As consumers, they furnish the demand for goods or services, niche and mass alike, that promise success in social and professional contexts.

Women and girls must try to make sense of two contradictory ‘progressive’ messages: ‘accept yourself as you are’ and ‘you can be whatever you want’. The tension evokes Oscar Wilde’s ‘be thyself’. And as Wilde argued, hierarchy and systemic inequality make the proposition impossible for rich and poor alike – or, for that matter, men and women. Accepting yourself as you are also means accepting your own wishes for development; to experiment, rebel and become what you desire. In body politics, it means to self-assess and devise your own criteria and values in how you present yourself to others. But this process is affected by wider sociopolitical structures and institutions.

In liberal capitalism, being ‘what you want to be’ is easily skewed by concepts of self-advancement, equal opportunity, social mobility and entrepreneurship. Individuals are somehow free to live their best lives when they don’t challenge the prevailing norms and distributions of power. In fact, the best life is to be a CEO, president, military leader, fashion editor, supermodel or influencer – a ‘girlboss’. On the other hand, dissident values end up being outlawed, demonised or ridiculed. This is the historical experience of all marginalised groups, including trans-communities.

Anarchafeminists talk about self-expression and becoming but also about the impediments to the mutual aid that allows and encourages individuals to embrace their uniqueness as social beings. J.S. Mill argued that challenging norms, breaking ranks and finding new ways of living is the lifeblood of a dynamic, vibrant society. Anarchist women shared his view. Hundreds refused to marry, chose to have their children out of wedlock, wore their hair short and shared information about contraception and abortion, risking ostracism and imprisonment as a result. But for anarchists, Mill’s principles of non-interference and the minimisation of harm are imperfect instruments for creativity because they assume state enforcement and market competition. Anarchafeminists argue that individual well-being cannot be disconnected from collective social change.

This is the bridge that anarchafeminism helps us to cross as a solution to all the anxiety and depression people are suffering about conforming to homogenising, repressive norms. The cosmetics multinational L’Oréal uses the strapline ‘you’re worth it’ to peddle its products. De Cleyre’s views on women’s liberation provide the perfect foil: ‘women are not worth it until they take it’.